Introduction

The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is a herpesvirus transmitted mainly through close contact, particularly via saliva, from an infected individual.[1] Primary infection is often asymptomatic but may manifest as infectious mononucleosis. This condition is classically characterized by a triad of fever, tonsillar hypertrophy, and cervical lymphadenopathy. However, other symptoms such as myalgia, palatal petechiae, or organomegaly may also occur, and the classical triad may be incomplete in some cases.[2]

Serological testing confirms the diagnosis by detecting anti–viral capsid antigen (VCA), IgM antibodies specific to EBV. In the general adult population, EBV seropositivity is very common, with 90–95% of individuals exhibiting VCA IgG antibodies due to prior immunization or past infection.[3]

Thrombocytopenia is defined as a platelet count below 150 × 10⁹/L. It is often asymptomatic when mild, but moderate thrombocytopenia (50–99 × 10⁹/L) may present with non-blanching petechiae or ecchymoses. When platelet counts fall below 50 × 10⁹/L, the risk of severe hemorrhage—including gastrointestinal, urinary, or intracranial bleeding—increases significantly, often accompanied by hemorrhagic oral bullae.

Thrombocytopenia may result from decreased platelet production (central causes) or increased peripheral destruction. Peripheral mechanisms include immune-mediated platelet destruction, excessive platelet consumption due to thrombus formation, splenic sequestration, hemodilution, or in vitro platelet aggregation during sample analysis.[4]

Case presentation

A 27 years-old man with no significant medical history or allergies presented with fever (102.2 °F), left lumbar pain and dysuria for five days. He was referred to the emergency department for suspected pyelonephritis. On examination, he was hemodynamically stable and febrile (102 °F) with no lumbar tenderness or signs of sepsis.

Urine dipstick testing showed mild ketonuria without leukocyturia or hematuria. Laboratory results revealed thrombocytopenia (39 × 10⁹/L) with normal hemoglobin, mild inflammatory response (CRP 49 mg/L), and no leukocytosis. The automated hematology analyzer (pocH-100™) reported an error in leukocyte differentiation, and repeated tests confirmed persistent thrombocytopenia (58 × 10⁹/L).

The patient was discharged with ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily for 14 days, acetaminophen for fever, and instructions for repeat testing after 48 hours.

Two days later, he returned to the emergency department with persistent bleeding from the venipuncture site lasting more than one hour. Physical examination revealed hemorrhagic oral bullae and purpura on the upper limbs. He reported diffuse myalgia but no neurological or abdominal symptoms. Laboratory testing showed profound thrombocytopenia (< 5 × 10⁹/L).

Comprehensive investigations, including blood cell count, coagulation profile, renal and hepatic function tests, and thoraco-abdomino-pelvic contrast-enhanced CT were performed. Imaging revealed marked splenomegaly.

A bone marrow aspiration was attempted twice without success (Figure 1).

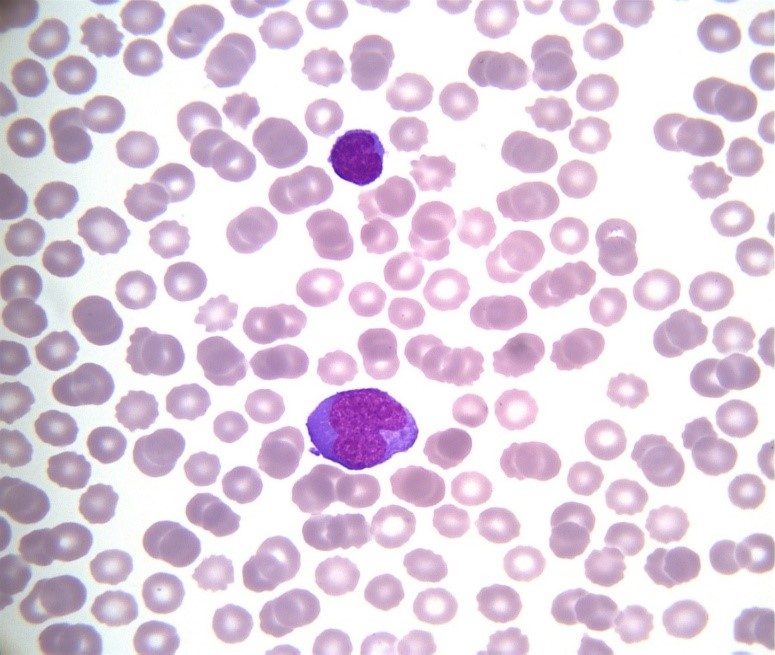

Peripheral blood smear revealed activated hyperbasophilic lymphocytes, compatible with infectious mononucleosis (Figure 2).

Serologic testing confirmed acute EBV infection. No other cytopenias were observed, and hemolysis markers were normal, ruling out TMA or DIC. Given the isolated severe thrombocytopenia and evidence of acute EBV infection, immune thrombocytopenia related to infectious mononucleosis was diagnosed.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for close monitoring due to the high risk of hemorrhage and splenic rupture. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy was initiated, followed by intravenous corticosteroids at 1 mg/kg/day, later transitioned to oral corticosteroids with tapering (40 mg daily for one week, then 20 mg daily for one week). Folic acid supplementation and weekly platelet count monitoring were prescribed.

The patient showed rapid clinical improvement, with cessation of bleeding and progressive normalization of platelet counts. He was discharged after six days of hospitalization with outpatient follow-up. No relapse or further complications were reported during follow-up.

Discussion

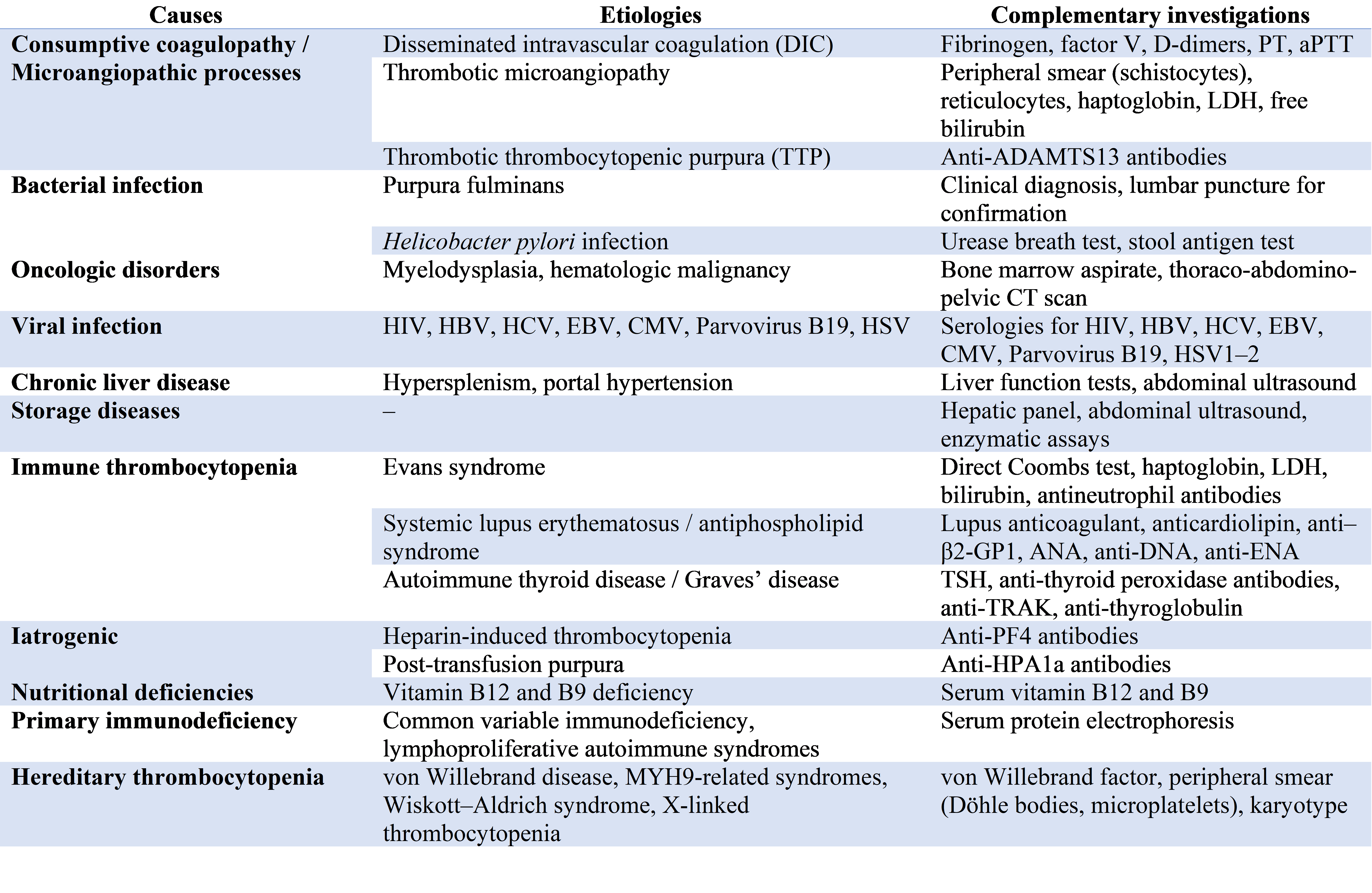

Thrombocytopenia discovered in the emergency department must not be underestimated. False thrombocytopenia due to platelet clumping must first be excluded, either by repeating the blood draw in a sodium citrate tube or by performing a manual platelet count by a trained biologist. Etiology of thrombocytopenia must be determined with the help of relevant diagnostic investigations (Table 1).

The initial diagnostic work-up should include a complete blood count, C-reactive protein (CRP), renal and hepatic function tests, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), haptoglobin, bilirubin, and coagulation studies with fibrinogen dosage, factor V activity, D-dimer levels, prothrombin time (PT or Quick), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).

In the presence of clinical or laboratory signs of infection, further investigations should include blood cultures (in case of fever), as well as serologic testing for HIV, hepatitis A, B, and C viruses, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), and herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. Additional tests to consider include serum protein electrophoresis, thyroid function tests, vitamin B9 and B12 levels, Helicobacter pylori testing (urease breath test or stool antigen), and a contrast-enhanced thoraco-abdomino-pelvic CT scan, especially in cases of severe thrombocytopenia of unclear origin.

The emergency physician facing severe thrombocytopenia must promptly exclude life-threatening conditions such as purpura fulminans, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA).[5]

The diagnosis of purpura fulminans is primarily clinical and may be confirmed by lumbar puncture when appropriate. In cases of DIC, coagulation studies typically reveal prolonged PT and aPTT, elevated D-dimers, and decreased fibrinogen levels. When anemia is also present, the detection of schistocytes on the peripheral smear, along with elevated reticulocyte count, LDH, indirect bilirubin, and low haptoglobin, suggests mechanical hemolysis, consistent with a thrombotic microangiopathy.[6]

A decreased reticulocyte count, on the other hand, points toward a central production defect. In such cases, the peripheral smear may reveal circulating blasts suggestive of myelodysplastic syndrome or hematologic malignancy. Activated lymphocytes on the smear may orient the diagnosis toward infectious mononucleosis.[7]

A bone marrow aspiration should be performed promptly if central thrombocytopenia is suspected—especially in the presence of additional cytopenias or clinical signs of malignancy such as lymphadenopathy or organomegaly.

In contrast, an isolated thrombocytopenia associated with a compatible clinical presentation and no other abnormalities supports the diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) or viral etiology as such as EBV infection. In such cases, bone marrow aspiration is unnecessary, though it is more often performed in adults than in children when diagnostic uncertainty persists.[8]

Recent studies have reported an increasing incidence of infectious mononucleosis in developed countries due to delayed primary EBV infection. Consequently, more severe forms now occur in young adults without comorbidities. A French study demonstrated that the later the infection occurs, the higher the risk of hospitalization and longer hospital stay.[9]

In adults, diagnosis is often delayed because atypical or severe complications predominate, such as hepatosplenomegaly, severe odynophagia, jaundice, or neurological involvement. Laboratory findings may show intense inflammatory response, marked lymphocytosis, and hepatic cytolysis, suggesting a dysregulated immune reaction.

Complications include neurological syndromes (meningitis, encephalitis, Guillain–Barré), hepatic failure, hemolytic anemia, and severe thrombocytopenia. Life-threatening hemorrhagic events related to EBV-induced immune thrombocytopenia have been rarely described. Although usually benign, its complications can be severe and justify ICU admission for close observation.[10]

Conclusion

Thrombocytopenia discovered in the emergency department should never be overlooked. After ruling out purpura fulminans, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and thrombotic microangiopathy, an etiological work-up must be conducted promptly and comprehensively from the outset. This should include exclusion of hematologic malignancies and systematic evaluation for viral causes.

Given the increasing incidence of infectious mononucleosis among young adults, this differential diagnosis should be considered early to prevent unnecessary and invasive investigations. Although infectious mononucleosis is most often benign, potential complications must always be assessed, as some may be life-threatening and require admission to an intensive care unit for close monitoring.

Consent and ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication.

References

- Odumade OA, Hogquist KA, Balfour HH Jr. Progress and problems in understanding and managing primary Epstein-Barr virus infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011;24:193–209.

- Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1993–2000.

- Koçak M, Güven D. Complications of infectious mononucleosis in children. Med J Islam World Acad Sci 2020;28:61–71.

- Gauer RL, Whitaker DJ. Thrombocytopenia: evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician 2022;106:288–98.

- Ashworth I, Thielemans L, Chevassut T. Thrombocytopenia: the good, the bad and the ugly. Clin Med (Lond). 2022 May;22(3):214-217. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2022-0146. PMID: 35584828; PMCID: PMC9135082.

- Arnold DM, Patriquin CJ, Nazy I. Thrombotic microangiopathies: a general approach to diagnosis and management. CMAJ. 2017 Jan 30;189(4):E153-E159. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160142. Epub 2016 Oct 17. PMID: 27754896; PMCID: PMC5266569.

- Pinto MPB. Infectious mononucleosis by Epstein-Barr virus: A complete laboratory picture. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2024 Apr-Jun;46(2):210-211. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2023.10.002. Epub 2023 Dec 5. PMID: 38065725; PMCID: PMC11150483.

- Stensby JD, Long JR, Hillen TJ, Jennings JW. Safety of bone marrow aspiration and biopsy in severely thrombocytopenic patients. Skeletal Radiol. 2021 May;50(5):915-920. doi: 10.1007/s00256-020-03623-5. Epub 2020 Oct 4. PMID: 33011873.

- Hocqueloux L, Causse X, Valery A, et al. The high burden of hospitalizations for primary EBV infection: a 6-year prospective survey in a French hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015;21:1041.e1–1041.e7.

- Walter RB, Hong TC, Bachli EB. Life-threatening thrombocytopenia associated with acute Epstein-Barr virus infection in an older adult. Ann Hematol. 2002 Nov;81(11):672-5. doi: 10.1007/s00277-002-0557-1. Epub 2002 Oct 29. PMID: 12454710.