Introduction

Uterine rupture is a rare but serious obstetric emergency. It is characterized by a full-thickness disruption of the uterine wall which often results in significant maternal and fetal morbidity or mortality [1]. While the incidence is highest among women with a scarred uterus ( those with history of previous cesarean deliveries or myomectomies) cases of rupture in an unscarred uterus remain exceedingly rare. Most uterine ruptures occur in the third trimester or during labor and are typically associated with identifiable risk factors such as uterine trauma, multiparity, uterine anomalies or the use of uterotonic agents [2]. Prompt diagnosis of uterine rupture remains a challenge particularly when clinical presentations are atypical or when risk factors are absent.

Among women with a previously unscarred uterus spontaneous uterine rupture is particularly uncommon and unpredictable event. The challenge lies in the fact that such patients are generally not considered high-risk and the index of suspicion among clinicians for uterine rupture in these cases is usually low. This diagnostic bias may be responsible for delay in appropriate intervention which may compromise outcomes. Multiparity is known to be associated with increased uterine wall distensibility as well as myometrial thinning which may be a risk factor for rupture even in the absence of prior uterine surgery [3]. Advanced maternal age is another important contributing factor as studies suggest a higher rate of uterine rupture in women above 35 years of age [4].

Clinically, uterine rupture can be difficult to recognize, especially when classical signs such as vaginal bleeding, loss of fetal station, or sudden cessation of uterine contractions are absent. Among these, fetal distress which is usually evidenced by fetal bradycardia remains the most consistent and urgent clinical indicator [5]. Nonetheless, the condition may be misdiagnosed in the absence of traditional risk factors particularly in women with no history of uterine surgery. In rare instances, non-obstetric pelvic surgeries such as ovarian cystectomy or appendectomy have been considered possible contributors to altered pelvic anatomy or vascularization. These surgeries may in turn predispose to uterine wall compromise although a direct causal link has not been well established. Such associations makes it necessary to keep possibility of uterine rupture as a differential diagnosis in pregnant women who present with acute abdominal pain, irrespective of their obstetric history [6].

Despite the existence of well-established clinical guidelines for managing uterine rupture most are directed towards patients with previous cesarean sections or recognized uterine scars [7]. This leaves a considerable knowledge gap in addressing rupture in women without these known risk factors. Furthermore, unscarred uterine rupture may remain underreported, particularly in resource-limited settings where diagnostic facilities are constrained. As such, the true burden and spectrum of unscarred uterine rupture remain poorly understood as well as underdiagnosed.

Case presentation

A 40-year-old gravida 3, para 2+0 woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with a history of lower abdominal pain at 33 weeks and 1 day of gestation. She reported fetal movements to be adequate. There was no history of any per vaginal bleeding or leaking. Her obstetric history included two previous uneventful normal spontaneous vaginal deliveries (NSVDs). She had a surgical history of undergoing ovarian cystectomy and a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Both of these surgeries were performed several years back. She had no history of cesarean section or uterine instrumentation. At the time of arrival to hospital she was hemodynamically stable (blood pressure was 140/90 mmHg, heart rate 90 bpm) and afebrile. Abdominal examination showed presence of mild tenderness without presence of active uterine contractions. On pelvic examination, the os was closed and no bleeding or leaking was noted.

Cardiotocography (CTG) was classified as Category I (reassuring fetal status with no uterine contractions).8 A bedside obstetric ultrasound showed presence of a single viable fetus with appropriate biometry for gestational age. Placenta was located anteriorly and was reported to be safely away from os. Amniotic fluid volume was adequate. There was no evidence of placental abruption or retroplacental clots. Given the reassuring maternal and fetal parameters, the patient was discharged with instructions for close follow-up. A single course of corticosteroids was administered for fetal lung maturation in view of possibility of preterm delivery.

Approximately 12 hours later, the patient was brought back to the ED with complaints of severe, continuous abdominal pain. She appeared pale and her vital signs revealed presence of hypotension (BP 107/79 mmHg), tachycardia (HR 140 bpm) and mildly tachypnea. Generalized abdominal tenderness and guarding was also present. On auscultation fetal sounds could not be located. Her hemoglobin had dropped to 7.2 g/dL. A diagnosis of concealed placental abruption was initially made on the basis of clinical presentation and a massive transfusion protocol was activated in anticipation of possible emergency surgical intervention.

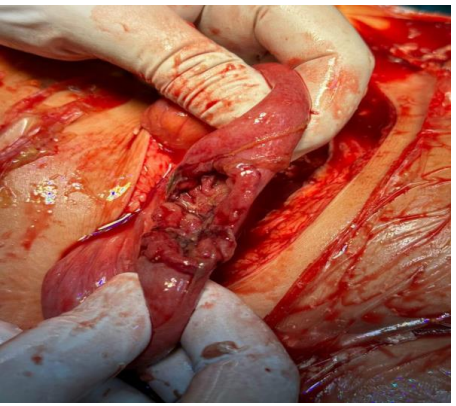

The patient was taken urgently for cesarean section under general anesthesia. intraoperatively approximately 4-5 Litres of blood and clots were evacuated from the peritoneal cavity. A 7 cm longitudinal fundal uterine rupture was identified with complete herniation of the placenta and fetus into the peritoneal cavity (Figure 1).

The fetus was delivered but was already demised in utero (intrauterine fetal demise, IUFD). The uterus was repaired in two layers. Intraoperatively there was no evidence of adhesions, scarring, or structural abnormalities related to her previous ovarian cystectomy. The patient received four units of packed red blood cells and two units of fresh frozen plasma intraoperatively.

Postoperatively, she was shifted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for monitoring and further management. Over the next 48 hours she developed serious complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), aspiration pneumonia and acute kidney injury (AKI). In view of her deteriorating condition, the patient was intubated and put on mechanical ventilation. Broad spectrum antibiotics were also started. She gradually improved with and was successfully extubated on postoperative day 7. Renal function stabilized without the need for dialysis.

The patient was discharged on day 14 and was in stable condition at the time of discharge. She was counselled regarding the potential risks of uterine rupture in future pregnancies and the need for delivery in a tertiary care facility with early planned cesarean delivery.

Discussion

In this case of a 40-year-old multiparous woman (gravida 3, para 2) with an unscarred uterus who developed a longitudinal fundal rupture at 33 +1 weeks several aspects of our findings are similar to cases reported in existing literature. Our observation that rupture occurred despite absence of prior cesarean or uterine instrumentation aligns with reports such as that by Sakr et al who described unscarred uterine rupture in a 38 years old multiparous women [9]. Similarly, Guèye et al documented that high parity (multiparity) is a recognized major risk factor for spontaneous rupture of unscarred uterus [10]. Thus, our case supports the notion that multiparity alone may suffice to predispose to such catastrophic events possibly due to cumulative myometrial stretching and thinning.

However, our patient lacked many of the common precipitating factors often reported in series of unscarred uterine rupture. There was no labor induction or augmentation, no use of uterotonics, no instrumental delivery, no obstructed or prolonged labor and there was no malpresentation. This mirrors recent reports such as those by Chen et al., who described three cases of spontaneous rupture in unscarred uteri in the absence of obvious risk factors or uterine interventions [11]. Additionally a case series by Halassy et al underscored that unscarred uterine rupture remains a rare but real possibility outside the classical context of prior uterine surgery or labor interventions [12]. These observations demonstrate that relying solely on known risk factors may result in delayed recognition when rupture occurs under apparently low-risk circumstances.

Rupture in this occurred in the preterm period (33 +1 weeks), which is less common but has been described. While many cases of unscarred uterine rupture occur at term or during labor, evidence suggests that rupture can occur in later gestation (third trimester) particularly in multiparous patients. A recent report by Rakama S et al described preterm unscarred uterus rupture in a multipara around 33 weeks of gestation [13]. This underlines that gestational age alone does not exclude risk of spontaneous uterine rupture and that clinicians should maintain vigilance even in preterm pregnancies.

In terms of maternal and perinatal outcomes, our case reflected the severe morbidity often associated with unscarred uterine rupture in resource-limited or delayed-diagnosis settings. The fetus could not be saved (intrauterine fetal demise) and the mother required massive transfusion, ICU care, mechanical ventilation and had complications including ARDS and AKI. This is consistent with previous findings: in a retrospective analysis of 13 cases of unscarred uterine rupture reported by Vernekar M et al. [14]. In this study maternal mortality was substantial and perinatal mortality exceeded 50%. Similarly, in a 2015 case series describing rupture of an unscarred uterus by O’Sullivan et al reported severe hemorrhage, fetal demise and considerable maternal morbidity [15]. Such data illustrate that despite the rarity of unscarred rupture the consequences can be devastating.

Finally, our case highlights important gaps in current clinical guidance. As noted in reviews, most management protocols and risk-assessment frameworks for uterine rupture focus on scarred uteri (e.g., prior cesarean, myomectomy) or on labor-related risk factors (induction/augmentation, obstructed labor, uterine overdistension). There remains a paucity of clinical tools to predict or screen for uterine rupture in unscarred uteri, especially in multiparous but otherwise low-risk women. Our report therefore supports the recommendation by Chen et al that any pregnant woman presenting with acute abdominal pain regardless of obstetric history should be evaluated with uterine rupture in differential diagnosis [11].

Conclusion

This case underscores that spontaneous rupture of an unscarred uterus, though rare, remains a critical diagnosis even in the absence of traditional risk factors. Multiparity and advanced maternal age may be sufficient to produce myometrial vulnerability. Given the catastrophic potential, obstetric care providers should maintain a high index of suspicion when encountering acute abdominal pain in pregnancy irrespective of gestational age and uterine scar status.

Consent and ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication.

References

- Togioka BM, Tonismae T. Uterine rupture. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

- You SH, Chang YL, Yen CF. Rupture of the scarred and unscarred gravid uterus: outcomes and risk factors analysis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;57(2):248-254. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2018.02.014

- Hochler H, Wainstock T, Lipschuetz M, et al. Grand multiparity, maternal age, and the risk for uterine rupture: a multicenter cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(2):267-273. doi:10.1111/aogs.13725

- Baek S, Froese V, Morgenstern B. Risk profiles and outcomes of uterine rupture: a retrospective and comparative single-center study of complete and partial ruptures. J Clin Med. 2025;14(14):4987. doi:10.3390/jcm14144987

- Woo JY, Tate L, Roth S, Eke AC. Silent spontaneous uterine rupture at 36 weeks of gestation. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2015;2015:596826. doi:10.1155/2015/596826

- Abdulmane MM, Sheikhali OM, Alhowaidi RM, Qazi A, Ghazi K. Diagnosis and management of uterine rupture in the third trimester of pregnancy: a case series and literature review. Cureus. 2023;15(6):e39861. doi:10.7759/cureus.39861

- Arusi TT, Zewdu Assefa D, Gutulo MG, Gensa Geta T. Predictors of uterine rupture after one previous cesarean section: an unmatched case-control study. Int J Womens Health. 2023;15:1491-1500. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S427749

- Alfirevic Z, Devane D, Gyte GM, Cuthbert A. Continuous cardiotocography as a form of electronic fetal monitoring for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:CD006066. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006066.pub3

- Sakr R, Berkane N, Barranger E, et al. Unscarred uterine rupture: case report and literature review. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2007;34(3):190-192.

- Guèye M, Mbaye M, Ndiaye-Guèye MD, et al. Spontaneous uterine rupture of an unscarred uterus before labour. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:598356. doi:10.1155/2012/598356

- Chen Y, Cao Y, She JY, et al. Spontaneous rupture of an unscarred uterus during pregnancy: a rare but life-threatening emergency. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(24):e33977. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000033977

- Halassy SD, Eastwood J, Prezzato J. Uterine rupture in a gravid, unscarred uterus: a case report. Case Rep Womens Health. 2019;24:e00154. doi:10.1016/j.crwh.2019.e00154

- Rakama S, Ondieki D. Preterm unscarred uterus rupture in a multipara: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol East Cent Africa. 2019;31:28-31.

- Vernekar M, Rajib R. Unscarred uterine rupture: a retrospective analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2016;66(Suppl 1):51-54. doi:10.1007/s13224-015-0769-7

- O’Sullivan R, Sauer C, Friedman P, Clark M, Menderes G. Rupture of the unscarred gravid uterus: case series. J Med Cases. 2015;6(7):330-332.