Introduction

Schwannomas are benign, encapsulated peripheral nerve sheath tumors that arise from Schwann cells and typically exhibit indolent growth. In the head and neck their clinical recognition can be difficult because they often present as a painless, slowly enlarging mass with few or no neurological symptoms. Most extracranial cervical schwannomas originate from the vagus nerve or the sympathetic chain and lesions arising from the hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII) are distinctly rare. This rarity matters clinically when a submandibular or upper neck swelling is encountered, clinicians and radiologists tend to prioritize far more common entities (salivary gland pathology, developmental cysts, inflammatory lymphadenopathy and mucous extravasation phenomena) before considering a nerve sheath tumor [1].

Plunging ranula represents one of the most frequent diagnostic “anchors” for a cystic mass in the submandibular region. Ranulas are mucoceles arising from the sublingual gland may extend through or around the mylohyoid muscle into the neck thereby producing a soft, fluctuant swelling in the submandibular space. Imaging often reinforces this impression particularly when a lesion appears predominantly cystic, insinuates along fascial planes and lies close to the sublingual gland. In every suspected plunging ranula, the lesion should be assessed for features typical of mucus in both its anatomical spread and biological behavior. Not all cystic-appearing neck masses originate from the salivary glands. Not all ranula-like lesions yield mucin or inflammatory cells on aspiration [2].

Schwannomas can mimic cystic lesions when they undergo degenerative change—such as cystic degeneration, hemorrhage, or myxoid alteration—especially in larger, long-standing tumors. In such settings, radiological hallmarks of schwannoma (a well-circumscribed, encapsulated, enhancing solid mass sometimes showing a “target” appearance) may be attenuated or absent and fine needle aspiration cytology may be non-specific or misleading because sampling preferentially captures hypocellular, degenerative fluid rather than diagnostic spindle cells. This creates a diagnostic trap: a cystic neck mass near the sublingual gland is labelled a ranula; an equivocal FNAC is interpreted as “consistent with cyst”. In these circumstances a definitive preoperative suspicion of a nerve-origin tumor may never arise [3].

The hypoglossal nerve’s anatomy further contributes to this pitfall. After exiting the hypoglossal canal, CN XII descends in the neck and courses anteriorly toward the tongue, passing through the submandibular region in close relationship to the carotid space structures, the posterior belly of the digastric and the submandibular gland area. A schwannoma arising along this extracranial segment can therefore present as a submandibular mass indistinguishable from salivary or cystic pathology. Importantly, hypoglossal nerve palsy (tongue deviation, atrophy, fasciculations, dysarthria) may be absent early or overlooked unless specifically sought, so the absence of neurological deficit does not reliably exclude hypoglossal involvement [4].

Given these uncertainties, histopathological evaluation remains the decisive step for diagnosis. Classic features—Antoni A and Antoni B areas, Verocay bodies, and strong S100 immunopositivity—confirm schwannoma and distinguish it from ranula and other cystic mimics. This report highlights a rare hypoglossal nerve schwannoma presenting as a cystic submandibular swelling initially considered a plunging ranula.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old man with no significant past medical history presented with a progressively enlarging swelling in the right submandibular region for last six months. This swelling was not associated with pain, fever, dysphagia, odynophagia, xerostomia or any other symptoms suggestive of salivary duct obstruction. There were no hoarseness of voice or neurological complaints. Additionally, patient did not notice any tongue deviation or speech disturbance.

On clinical examination, a well-defined swelling was noted in the right submandibular area. The mass measured approximately 3 × 3 cm. It was firm in consistency, non-tender and mobile. There was no overlying skin discoloration, warmth or sinus formation. The oral cavity examination did not reveal an obvious floor-of-mouth swelling and there were no clinically appreciable cranial nerve deficits on bedside assessment. There was no evidence of enlarged cervical lymph nodes.

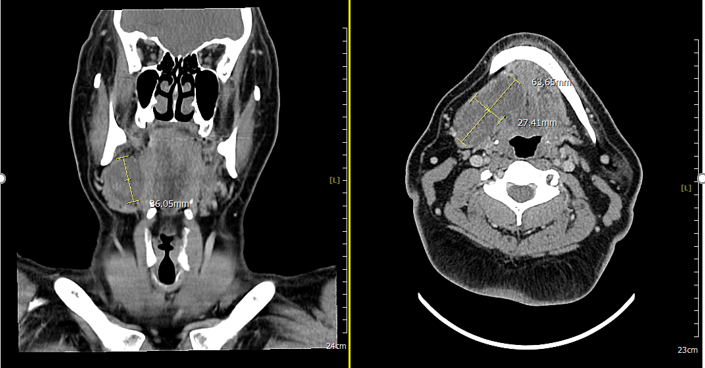

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was performed which was found to be non-contributory and did not show any atypical cells. Given the persistent, progressive nature of the swelling, contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) of the neck was done. It showed a well-circumscribed hypodense lesion in the right submandibular space measuring approximately 2.7 × 6.3 × 3.4 cm extending superiorly toward the sublingual region. The lesion abutted the mylohyoid and genioglossus muscles and was seen to be causing compression of the right submandibular gland without any radiological features of infiltration (Figure 1).

In view of its location and cystic appearance with sublingual extension a provisional diagnosis of plunging ranula was considered. The patient subsequently underwent surgical excision. The planned procedure comprised excision of the presumed plunging ranula along with sublingual gland removal and right sub-mandibulectomy. Intraoperatively, a cystic-appearing mass with a smooth surface and clear margins was identified and excised in toto. The lesion measured approximately 6.0 × 2.5 cm. The right submandibular gland, measuring approximately 3.0 × 2.0 cm, was also excised (Figure 2).

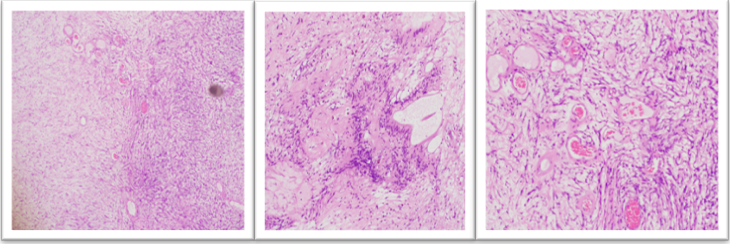

Histopathological evaluation of the submandibular gland revealed features of chronic sialadenitis with ductal dilatation and stromal fibrosis. Examination of the neck mass showed a well-circumscribed spindle cell neoplasm with alternating hypercellular Antoni A areas and hypocellular Antoni B areas. Verocay bodies were also identified. Additionally focal clusters of blood vessels with hyalinized walls were noted (Figure 3).

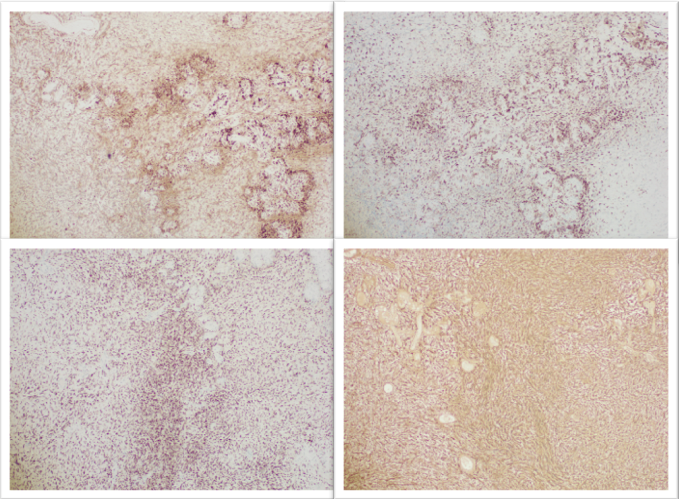

On immunohistochemistry the lesional cells showed diffuse positivity for S100 and SOX-10, supporting Schwann cell lineage while CD38 and CD163 were negative. The overall histomorphology and immunohistochemistry profile were diagnostic of schwannoma (Figure 4).

In the context of the lesion location and operative findings, the case represented an unusual hypoglossal nerve schwannoma clinically and radiologically masquerading as a plunging ranula.

Discussion

Schwannomas are benign encapsulated tumors that are derived from Schwann cells. Langner et al described head and neck Schwannomas as well circulated neoplasms with characteristic histologic Antoni A and Antoni B areas and strong S 100 immunopositivity. The authors emphasized that their clinical and radiological features are often non-specific thereby contributing to diagnostic uncertainty in unusual sites such as the submandibular region [5]. In our patient, the neck swelling was firm, non-tender and lacked any significant neurological deficit. These features closely mimicked common benign cystic masses like plunging ranula a pattern also reflected in the literature. Importantly the typically slow growing and asymptomatic nature of schwannomas often results in delayed diagnosis.

The rarity of hypoglossal nerve schwannomas in the extracranial neck and their propensity to imitate more common cervical masses has been previously documented but remains sparsely reported. Das et al. reported a 55 year old woman with a painless submandibular swelling initially interpreted as a submandibular gland neoplasm, later diagnosed postoperatively as a hypoglossal schwannoma on histopathology [6]. Similarly, Nassehi Y documented a case that simulated a salivary gland tumor, where imaging and initial diagnostics failed to establish a neurogenic origin before surgery [7]. These reports, similar to findings of our case report, illustrate that hypoglossal schwannomas can present without overt cranial nerve XII dysfunction and with imaging profiles that may resemble cystic lesions or salivary gland tumors. The absence of tongue deviation, dysarthria, or overt neurologic signs in both our patient and in previously published cases highlights the silent clinical behavior of extracranial schwannomas and the limitations of clinical examination alone in excluding a nerve sheath tumor.

Cystic degeneration within schwannomas further complicates the preoperative distinction from true cystic lesions such as plunging ranulas. Bohara et al reported that cystic change occurs in only a minority of schwannomas, approximately 4% of head and neck cases, but when present, can obscure classic solid radiologic features and mislead interpretation toward benign cysts [8]. Vallabh et al. described “ancient” schwannomas with prominent cystic components that closely resemble other fluid filled masses on imaging thereby increasing the possibility of misdiagnosis [9]. In our case, the lesion’s hypodense appearance on contrast enhanced CT and its insinuation into the submandibular compartment were interpreted as consistent with a plunging ranula a provisional diagnosis that guided surgical planning. This overlap underscores the necessity of integrating advanced imaging modalities (such as magnetic resonance imaging) which may enhance tissue characterization and nerve tract involvement more reliably than CT alone.

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) which is widely used in preoperative evaluation of neck masses can yield inconclusive results in schwannomas particularly when cystic or degenerative changes predominate. In our patient cytology was non-contributory and did not reveal diagnostic spindle cells likely because the aspirate predominantly consisted of acellular or hypocellular cystic fluid. Previous literature, including the case series by Parisi et al highlighted similar preoperative cytological limitations where schwannoma diagnosis was not confidently made without surgical excision and tissue analysis [10]. Some authors have noted that cytology showing benign spindle cells can raise suspicion for a neurogenic tumor, facilitating preoperative planning however this requires a high index of suspicion and expertise in differentiating from other spindle cell lesions. These observations show that while FNAC can be helpful it should not be solely relied upon to exclude schwannoma.

Histopathological evaluation remains the gold standard for definitive diagnosis and is important not only for distinguishing schwannoma from ranula or other cystic mimics. Moreover, histopathology also helps in identifying characteristic morphological features such as Antoni A and B areas, Verocay bodies and strong S100 positivity. These diagnostic criteria were clearly demonstrated in the present case. Given the potential surgical implications recognizing schwannomas pre or intraoperatively is critical. Surgeons should maintain a broad differential diagnosis for cystic appearing neck masses and when imaging or cytology is equivocal plan for intraoperative frozen section or prepare for nerve preserving techniques. Complete excision remains the definitive treatment and offers excellent prognosis with recurrence being rare in benign schwannomas when adequately removed.

Conclusion

Hypoglossal nerve schwannoma is a rare but important mimic of plunging ranula, particularly when cystic degeneration predominates. A cystic submandibular mass with sublingual extension and a non-diagnostic FNAC can mislead clinicians toward salivary mucous pathology. Definitive diagnosis depends on histopathology and immunohistochemistry (Antoni A/B areas, Verocay bodies, strong S100/SOX10 positivity). Preoperative diagnosis is crucial for appropriate surgical planning, facilitating nerve-preserving dissection and avoidance of unnecessary gland excision.

Consent and ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication.

References

- Majumder A, Ahuja A, Chauhan DS, Paliwal P, Bhardwaj M. A clinicopathological study of peripheral schwannomas. Med Pharm Rep. 2021 Apr;94(2):191-196. doi: 10.15386/mpr-1708. Epub 2021 Apr 29. PMID: 34013190; PMCID: PMC8118219.

- Dive AM, Bodhade AS, Mishra MS, Upadhyaya N. Histological patterns of head and neck tumors: An insight to tumor histology. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014 Jan;18(1):58-68. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.131912. PMID: 24959039; PMCID: PMC4065450.

- Dietrich EM, Vasilios B, Maria L, Styliani P, Konstantinos A. Sublingual-plunging ranula as a complication of supraomohyoid neck dissection. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2011;2(6):90-2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.02.005. Epub 2011 Mar 3. PMID: 22096692; PMCID: PMC3199698.

- Zurale MM, Patil A. A Rare Case of Hypoglossal Nerve Schwannoma Presenting as Hemiatrophy of the Tongue: A Case Report. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2023 Jan-Feb;26(1):76-77. doi: 10.4103/aian.aian_876_22. Epub 2023 Jan 17. PMID: 37034045; PMCID: PMC10081562.

- Langner E, Del Negro A, Akashi HK, Araújo PP, Tincani AJ, Martins AS. Schwannomas in the head and neck: retrospective analysis of 21 patients and review of the literature. Sao Paulo Med J. 2007 Jul 5;125(4):220-2. doi: 10.1590/s1516-31802007000400005. PMID: 17992392; PMCID: PMC11020543.

- Das A, Ganesan S, Raja K, Alexander A. Hypoglossal schwannoma in the submandibular region. BMJ Case Rep. 2021 May 26;14(5):e242225. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-242225. PMID: 34039548; PMCID: PMC8160155.

- Nassehi Y, Rashid A, Pitiyage G, Jayaram R. Floor of mouth schwannoma mimicking a salivary gland neoplasm: a report of the case and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2021 Feb 19;14(2):e239452. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-239452. PMID: 33608339; PMCID: PMC7896616.

- Parisi FM, Maniaci A, Broggi G, Salvatorelli L, Caltabiano R, Lavina R. Unmasking Hypoglossal Nerve Schwannomas Mimicking Submandibular Salivary Gland Tumors: Case Report of a Rare Presentation and Surgical Management. Surgeries. 2023; 4(4):522-529. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries4040051

- Bohara S, Dey B, Agarwal S, Gupta R, Khurana N, Gulati A. A case of cystic schwannoma in the neck masquerading as branchial cleft cyst. Rare Tumors. 2014 Aug 4;6(3):5355. doi: 10.4081/rt.2014.5355. PMID: 25276321; PMCID: PMC4178274.

- Vallabh N, Srinivasan V, Hughes D, Agbamu D. Ancient schwannoma in the sublingual space masquerading as a plunging ranula. J Surg Case Rep. 2017 Apr 4;2017(4):rjx068. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjx068. PMID: 28458873; PMCID: PMC5400499.