Introduction

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) is an uncommon and usually sporadic congenital disorder. It is characterized by the coexistence of vascular malformations and pigmentary mosaicism which most commonly is a capillary malformation (nevus flammeus/port-wine stain) seen in combination with dermal melanocytosis (Mongolian spots and nevus of Ota) [1]. The condition is thought to arise from aberrant development and migration of neural crest–derived melanocytes with concomitant vascular dysgenesis. This produces a combined pigmentary–vascular phenotype. Although many patients have predominantly cutaneous findings extracutaneous involvement has also been documented. This extracutaneous involvement may include neurological, ophthalmological, musculoskeletal and vascular abnormalities. Reported associations include seizures, cortical atrophy, leptomeningeal angiomatosis (Sturge–Weber spectrum), glaucoma and complex vascular malformations [2].

PPV has been categorized into multiple types (I–V) with subgroups based on whether lesions are limited to skin or accompanied by systemic involvement. Subsequently, Happle proposed a revised classification grounded in descriptive phenotypes such as phacomatosis cesioflammea and phacomatosis cesiomarmorata, the latter corresponding to the combination of cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and dermal melanocytosis [3]. Because PPV is rare, evidence guiding obstetric and anesthetic management is limited to small series and isolated case reports.

Physiological changes which take place in pregnancy may unmask or exacerbate vascular symptoms and peripartum period carries heightened thromboembolic risk in these cases. This risk of thromboembolism is more in patients with prior deep venous thrombosis or those receiving anticoagulation [4]. From an anesthetic perspective, neuraxial techniques can be advantageous for cesarean delivery however their safety hinges on careful exclusion of spinal or intracranial vascular malformations. Moreover, assessment of neurological status and adherence to anticoagulation timing to minimize the risk of neuraxial hematoma is also crucial in these cases. Ophthalmic involvement (e.g., glaucoma) also warrants attention when choosing techniques that may influence hemodynamics or venous pressures [5].

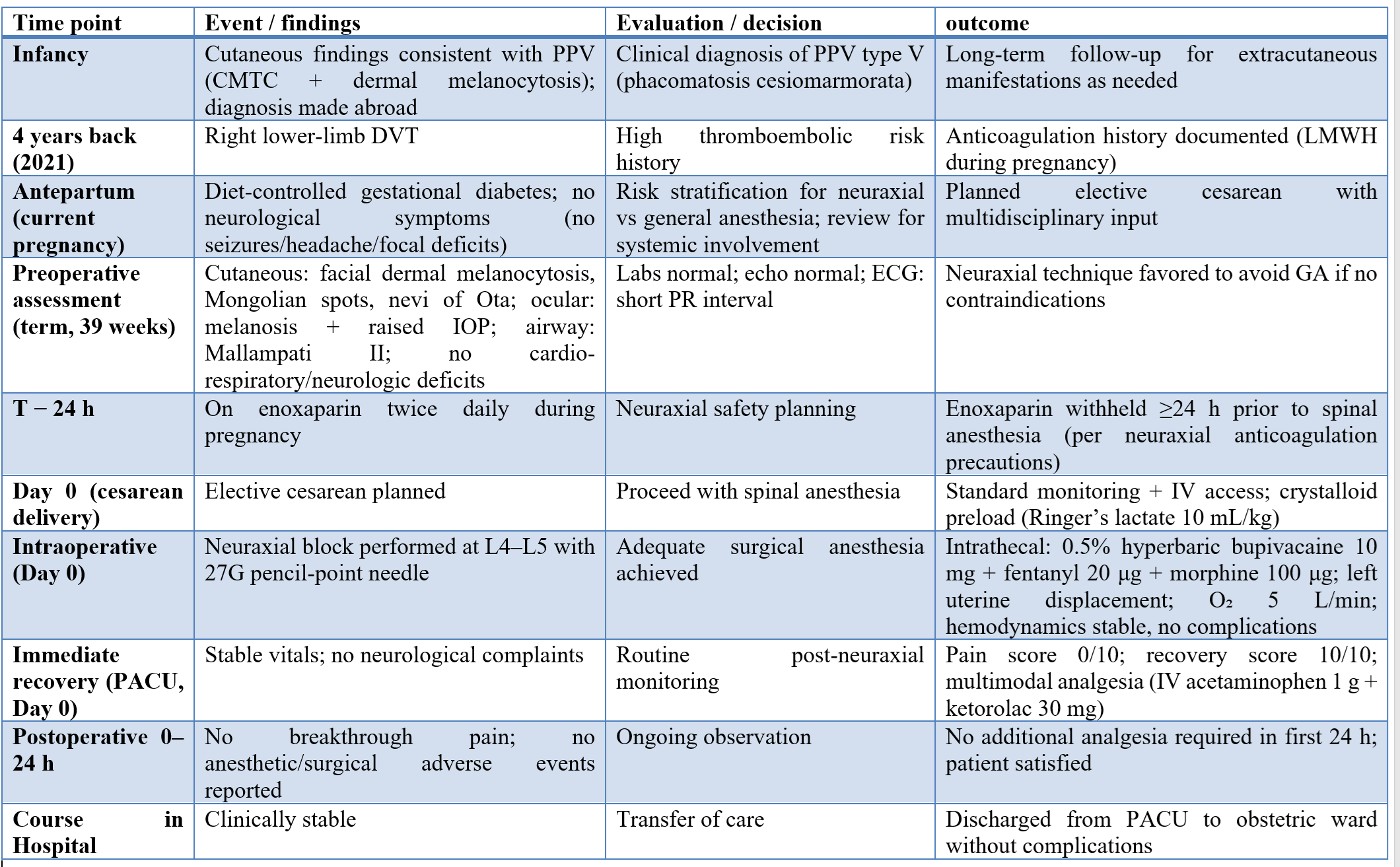

We present the case of a 30-year-old primigravida at 39 weeks’ gestation with PPV type V (phacomatosis cesiomarmorata), characterized by cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and dermal melanocytosis, who underwent elective cesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia. Her pregnancy was otherwise uneventful except for diet-controlled gestational diabetes. Her medical history included bilateral ocular melanosis with raised intraocular pressure and a previous right-leg deep venous thrombosis. She was receiving enoxaparin 0.4 mg twice daily, brinzolamide eye drops and cetirizine. Enoxaparin was discontinued 24 hours before surgery according to neuraxial anesthesia safety recommendations.

Case presentation

A 30-year-old primigravida at 39 weeks’ gestation with a childhood diagnosis of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) type V (phacomatosis cesiomarmorata) was admitted for an elective cesarean delivery. The diagnosis had been established in infancy based on characteristic cutaneous findings consistent with cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (CMTC) coexisting with dermal melanocytosis. Her medical history was notable for bilateral ocular melanosis with raised intraocular pressure and a prior episode of right lower-limb deep venous thrombosis 4 years back. During the current pregnancy, she developed gestational diabetes controlled which could be controlled with diet alone.

Her regular medications included subcutaneous enoxaparin (0.4 mL/40 mg) twice daily, brinzolamide ophthalmic drops, and cetirizine. In accordance with neuraxial anesthesia safety recommendations, enoxaparin was withheld 24 hours before surgery. On examination, she had bilateral facial dermal melanocytosis with Mongolian spots and nevi of Ota. Cardiovascular, respiratory and neurological examinations were unremarkable. Airway assessment revealed Mallampati class II. Preoperative laboratory investigations, including complete blood count and coagulation profile, were within normal limits. Transthoracic echocardiography showed no significant structural or functional cardiac abnormality. A 12-lead electrocardiogram demonstrated a short PR interval. No other ECG abnormalities could be documented. Obstetric ultrasound confirmed a term singleton pregnancy with no fetal concerns. Prior neuroimaging and genetic testing were not available because earlier investigations had been performed outside the treating institution.

After multidisciplinary discussion (obstetrics, anesthesiology, and ophthalmology), a neuraxial technique was selected to avoid general anesthesia. On arrival in the operating room, standard monitoring (electrocardiography, non-invasive blood pressure, and pulse oximetry) was instituted and a peripheral intravenous line was secured. The patient received crystalloid preload with Ringer’s lactate (10 mL/kg). With the patient in the sitting position, spinal anesthesia was given at the L4–L5 interspace using a 27-gauge pencil-point needle under strict asepsis. After free flow of cerebrospinal fluid was confirmed, intrathecal anesthesia was administered using 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine 10 mg with fentanyl 20 μg and morphine 100 μg. The patient was positioned supine with left uterine displacement and supplemental oxygen (5 L/min) was started via face mask.

Surgical anesthesia was achieved and the cesarean delivery proceeded uneventfully. Intraoperative hemodynamics remained stable, and no features suggestive of raised intracranial pressure or neurological compromise were observed. Postoperative multimodal analgesia was given which comprised of intravenous acetaminophen 1 g and ketorolac 30 mg. Recovery in the post-anesthesia care unit was uncomplicated. She required no additional analgesia during the first 24 hours and was discharged to the obstetric ward in stable condition.

Discussion

This case represents the use of spinal anesthesia for cesarean section in a full-term pregnant woman who was a diagnosed case of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) type V since infancy. PPV is a rare congenital disorder which is characterized by pigmentary and vascular anomalies along with potential systemic involvement including neurological as well as ocular abnormalities. Due to its rarity, anesthetic management guidelines is limited to isolated case reports or small case series [5]. In our patient there was history of ocular melanosis causing raised intraocular pressure. Also, there was a prior episode of deep venous thrombosis which necessitated thorough multidisciplinary evaluation prior to anesthesia.

An interesting observation in this case was the presence of a short PR interval documented on ECG which was a feature not previously associated with PPV. While it did not affect intraoperative management, this finding emphasizes the importance of complete cardiac evaluation. To our knowledge, there are no prior reports describing cesarean delivery under neuraxial anesthesia in a PPV patient.

Published literature supports the need for comprehensive screening in PPV and similar vascular disorders. Peláez et al has reported cases of PPV with systemic involvement [6]. These case report emphasize that cutaneous manifestations may be associated with deeper pathology. In our case, absence of neurologic symptoms and unremarkable cardiovascular and neurologic exams allowed us to consider neuraxial anesthesia. Comparative literature in patients with intracranial vascular abnormalities (e.g., AVMs) shows that neuraxial anesthesia can be safely used when imaging excludes high-risk lesions, as demonstrated by Cho et al [7]. Conversely, Brady et al. advocate for caution in disorders such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia since neuraxial vascular malformations in these cases may contraindicate use of spinal techniques for anesthesia [8].

Enoxaparin was discontinued 24 hours before scheduled surgery to prevent complications such as neuraxial hematoma. Neuraxial anesthesia also offered advantages in preventing airway complications and providing effective postoperative analgesia. The American Society of Anaesthesiologists also recommends that neuraxial anesthesia should be preferred for cesarean section [9]. However systemic conditions should be appropriately managed in these cases before arriving at a decision to give neuraxial anesthesia in these cases.

Postoperatively patient had a stable and uneventful recovery with effective pain control. Post-operative course in this case is similar to other reports where neuraxial techniques provided hemodynamic stability and minimized complications. Yilmaz et al. emphasized that individualized anesthetic planning and careful exclusion of contraindications are important in patients with rare neurologic or vascular disorders [10].

Conclusion

This case demonstrates that neuraxial anesthesia can be safely and effectively given in a parturient with phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. However, a detailed pre-operative workup is essential to exclude systemic involvement. Comprehensive preoperative evaluation and strict perioperative monitoring is essential for achieving favorable outcomes and avoiding post-operative complications.

Consent and ethics

Ethics Approval was waived, but confidentiality was ensured, and informed consent was obtained from our case

References

- Singh A, Chandan Y, Pazare AR. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis: a rare disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 2023;71(12):91-92. doi:10.59556/japi.71.0419

- Sánchez-Espino LF, Ivars M, Antoñanzas J, Baselga E. Sturge-Weber syndrome: a review of pathophysiology, genetics, clinical features, and current management approaches. Appl Clin Genet. 2023;16:63-81. doi:10.2147/TACG.S363685 Erratum: Sturge-Weber syndrome: a review of pathophysiology, genetics, clinical features, and current management approaches. Appl Clin Genet. 2024;17:131-132. doi:10.2147/TACG.S487419

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(3):385-388. doi:10.1001/archderm.141.3.385

- Chagas CAA, Pires LAS, Babinski MA, Leite TFO. Klippel-Trenaunay and Parkes-Weber syndromes: two case reports. J Vasc Bras. 2017;16(4):320-324. doi:10.1590/1677-5449.005417

- Nanda A, Al-Abdulrazzaq HK, Habeeb YK, Zakkiriah M, Alghadhfan F, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis: report of four new cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82(3):298-303. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.178905

- Viada Peláez MC, Stefano PC, Cirio A, Cervini AB. Facomatosis pigmentovascular tipo cesioflammea: a propósito de un caso. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2018;116(1):e121-e124. doi:10.5546/aap.2018.e121. (in Spanish)

- Cho D, Johnson AL, Pasternak JJ, Welch TL, Sharpe EE. Obstetric and anesthetic management of parturients with intracranial neurovascular abnormalities. J Anesth. Published online December 4, 2025. doi:10.1007/s00540-025-03631-6

- Brady S, Tan T, O’Flaherty D. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia and neuraxial anaesthesia in pregnancy: when should magnetic resonance imaging be performed? Anaesth Rep. 2023;11(1):e12227. doi:10.1002/anr3.12227

- Vallejo MC, Kumaraswami S, Zakowski MI. American Society of Anesthesiologists 2023 guidance on neurologic complications of neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia in obstetrics. Anesthesiology. 2024;140(6):1235-1236. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000004967

- Yilmaz MA, Uzun N. Neuraxial anesthesia in pregnant patients with neurological disorders: safety and practice strategies: a review. Chall J Perioper Med. 2025;3(1):14-20. doi:10.20528/cjpm.2025.01.003