Introduction

Severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome (SCID) is an uncommon inborn error of immunity, that typically results in fatality during infancy and predisposes individuals to severe, life-threatening infections.[1] SCID has a low incidence rate, estimated at approximately 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 1,00,000 live births.[2] The most common indicator of immunodeficiency in children is recurrent infections occurring more frequently than expected and affecting multiple sites.[3] Additionally, a single severe, opportunistic, or unusual infection can serve as an initial indicator of immunodeficiency. Roseomonas is a gram-negative, slow-growing, aerobic, non-fermentative bacteria characterized by their distinctive pink-pigmented colonies. They are generally opportunistic pathogens with limited pathogenic potential. A notable increase in reported human infections over the past two decades, particularly among immunocompromised individuals have been reported.[4] Here, we present the case of a 40-day old child diagnosed with T- B+ NK- SCID.

Case presentation

A 40-day-old male infant, weighing 4.75 kg, was referred with a 5-day history of fever and urinary tract infection, with urine culture showing insignificant growth of Klebsiella pneumoniae. The child had been treated for 2 days with piperacillin-tazobactam, and amikacin. Clinical examination did not reveal an obvious source of infection, although the liver was palpable 3 cm below the right costal margin. Blood investigations revealed anemia, leukocytosis, and significantly elevated C-reactive

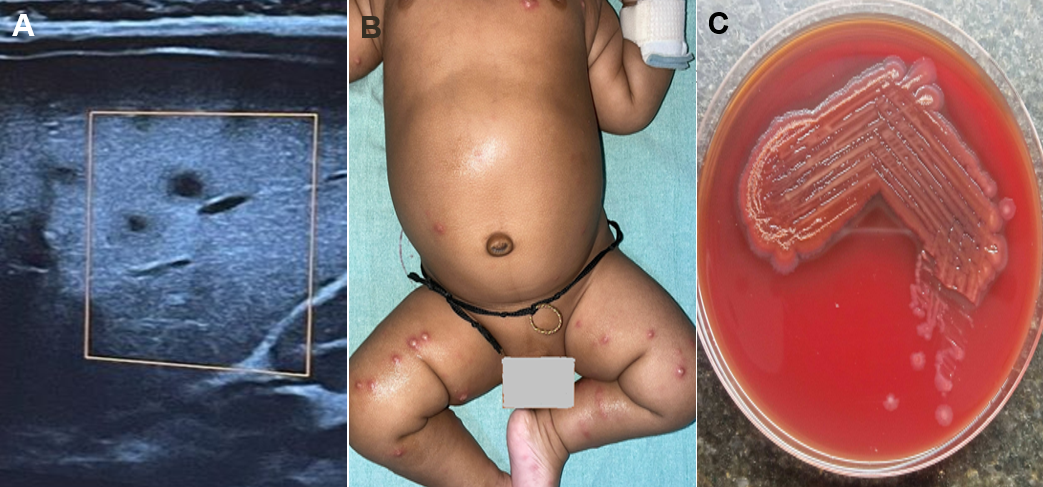

protein. The child was started empirically on cefuroxime, amikacin, and antipyretics. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis was normal. The child had ongoing fever spikes without a clear focus, hence high-resolution ultrasound of the abdomen and pelvis revealed multiple hepatic abscesses measuring 3-5 mm, likely pyogenic (Figure 1 A). Blood cultures obtained on day 5 showed no significant growth. However, on day 6, the child developed multiple pustular lesions on the ear, trunk, and extremities (Figure 1B). By day 7, blood culture revealed the growth of a slow-growing Roseomonas species, a member of the acetobacteraceae family, which grew within 7 days of incubation. The VITEK identification system confirmed the organism as Roseomonas species (Figure 1C).

The child showed clinical improvement, and a repeat ultrasound revealed small hypoechoic lesions in the liver, indicating resolving abscesses. On follow-up after 2 weeks, the child was afebrile, had gained weight, and a repeat abdominal ultrasound was normal. Due to hepatic abscesses and an unusual bacterial infection, the possibility of an inborn error of immunity was considered. The child had a history of recurrent respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, and cutaneous infections, all requiring oral antibiotics. At 9 months of age, the child presented with fever and cough. Blood tests showed moderate microcytic hypochromic anemia, neutrophilic leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, and elevated inflammatory markers. The child was treated with antibiotics, antipyretics, and bronchodilator nebulizations. A nasopharyngeal PCR swab was positive for Pneumocystis jiroveci and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Additionally, the child had hypopigmented patches on the neck and trunk, suggestive of a candidial infection. An immunodeficiency panel revealed low levels of CD3, CD56 cells, and immunoglobulins, suggesting SCID. A chest X-ray confirmed the absence of the thymus. The child was started on antibiotics, antivirals, and monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusions. He was referred for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) at a specialized center. Whole exome sequencing revealed an IL2RG-related disease, with a stop-gain variant observed in exon 7 of IL2RG in the hemizygous state, inherited from the mother.

Discussion

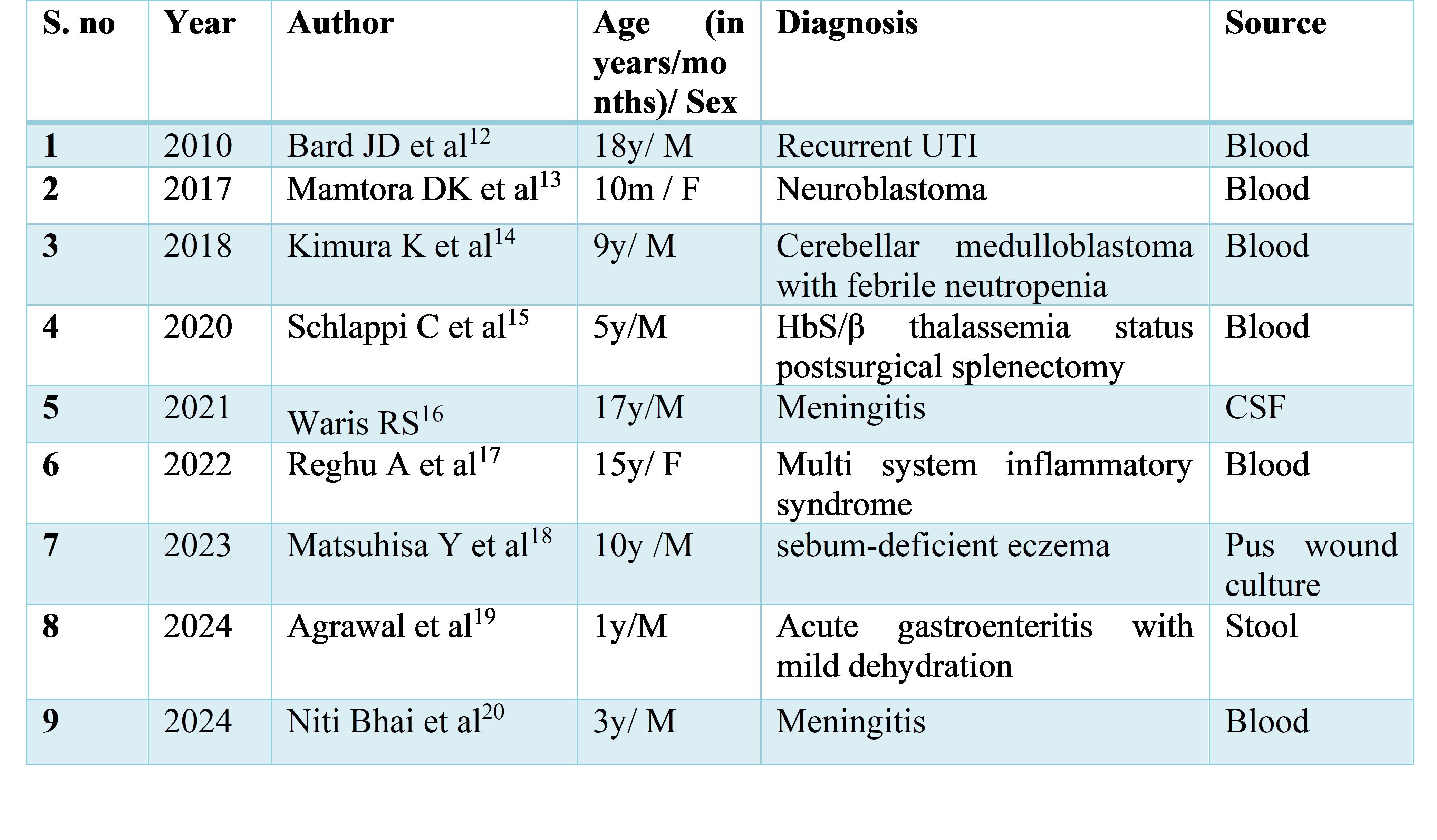

Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) is characterized by severe T-cell deficiency with variable B and NK-cell involvement, representing the most severe congenital immunodeficiency. Without achieving immunological reconstitution through interventions like bone marrow transplantation or enzyme replacement, death typically occurs before the age of one. SCID encompasses various types, clinically classified as T-B+ or T-B- SCID depending on B cell involvement, all presenting with low to absent T cell levels. The X-linked form is the most common, presenting as T-B+ NK- SCID, characterized by diminished T cells, normal B cell levels, and reduced natural killer cells, as observed in our patient [5]. Infants with SCID commonly experience recurrent episodes of diarrhea, pneumonia, sepsis, and skin infections within the first months of life, often followed by failure to thrive. Our patient presented at 6 weeks of age with a hepatic microabscesses and uncommon bacterial infection. Viral infections such as varicella, measles, parainfluenza, CMV, Epstein-Barr virus, and fungal infections like Candida and Pneumocystis jirovecii are common [6]. They will typically have hypoplastic thymus tissue, and there is often adenoid, tonsil, and peripheral lymph node hypoplasia [7]. Initially, immunoglobulin levels may appear normal due to maternal antibodies [8]. Analyzing lymphocyte subpopulations aids in identifying the specific type of SCID. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is curative in the majority of patients receiving a human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched sibling donor [9]. Our patient had a rare slow-growing organism infection. A systematic review of all published cases of Roseomonas infections showed an overall mortality of 3%, with mortality attributed to Roseomonas at 1%. Roseomonas species rarely infect humans due to their low pathogenicity, and their clinical characteristics are still not fully understood [10]. Central lines are often common sites of infection for Roseomonas bacteremia in children. Opportunistic infections caused by R. mucosa have been associated with skin microbiota [11]. A review of the literature on reported Roseomonas infections in children is summarized in table 1.

Conclusion

Early evaluation with a high index of suspicion is key in diagnosing inborn errors of immunity in infants, especially with uncommon bacterial infections such as Roseomonas. Even if a child appears to be thriving, this does not rule out the possibility of inborn errors of immunity. Additionally, chest X-rays should be scrutinized for a narrow mediastinum and the absence of the thymus, both of which can be indicative of inborn errors of immunity.

Given the rarity of such presentations, this case contributes valuable insight to the literature on SCID and opportunistic infections, particularly Roseomonas bacteremia in immunocompromised children, and highlights the importance of vigilance in recognizing these rare but potentially life-threatening conditions.

Consent and ethics

Ethics Approval was waived, but confidentiality was ensured, and informed consent was obtained from Parents.

References

- Shah I. Severe combined immunodeficiency. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42(8):819.

- Puck JM. Neonatal screening for severe combined immunodeficiency. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23(6):667-673.

- Heimall J, Cowan MJ. Long-term outcomes of severe combined immunodeficiency: therapy implications. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13(11):1029-1040.

- Purushotham P, Mahapatra A, Jafri N, Satapathy A. Unveiling the Uncommon: Roseomonas gilardii Bacteremia in a 10-Month Infant Presenting With Febrile Seizure. Cureus. 2025 Jul 8;17(7):e87503. doi: 10.7759/cureus.87503. PMID: 40777703; PMCID: PMC12329693.

- Fischer A. Severe combined immunodeficiencies (SCID). Clin Exp Immunol. 2000 Nov;122(2):143-9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01359.x.

- Vignesh P, Rawat A, Kumrah R, Singh A, Gummadi A, Sharma M, et al. Clinical, immunological, and molecular features of severe combined immune deficiency: a multi-institutional experience from India. Front Immunol. 2021 Feb 8; 11:619146.

- Soma S, Sullivan E. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22nd ed. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier; 2021. p. 1251-1364.

- Kwan A, Puck JM. History and current status of newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency. Semin Perinatol. 2015 Apr;39(3):194-205.

- Wahlstrom JT, Dvorak CC, Cowan MJ. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for severe combined immunodeficiency. Curr. Pediatr. Rep. 2015 Mar;3(1):1-0.

- Ioannou P, Mavrikaki V, Kofteridis DP. Roseomonas species infections in humans: a systematic review. J Chemother. 2020 Jul 3;32(5):226-36.

- Shokar NK, Shokar GS, Islam J, Cass AR. Roseomonas gilardii infection: case report and review. J Clin Microbiol. 2002 Dec;40(12):4789-91. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4789-4791.2002. PMID: 12454198; PMCID: PMC154581.

- Bard JD, Deville JG, Summanen PH, Lewinski MA. Roseomonas mucosa isolated from bloodstream of a pediatric patient. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(8):3027-3029. doi:10.1128/JCM.02349-09

- Mamtora DK, Mehta P, Bhalekar P. Roseomonas gilardii bacteraemia in a pediatric oncology patient on chemotherapy: a rare case report. Indian J Neonatal Med Res. 2017;5(2):PC01-PC03. doi:10.7860/IJNMR/2017/25839.2204

- Kimura K, Hagiya H, Nishi I, Yoshida H, Tomono K. Roseomonas mucosa bacteremia in a neutropenic child: a case report and literature review. IDCases. 2018;14:e00469. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2018.e00469

- Schlappi C, Bernstock JD, Ricketts W, Nix GA, Poole C, et al. Roseomonas gilardii bacteremia in a patient with HbSβ⁰-thalassemia: clinical implications and literature review. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2020;42(5):e385-e387. doi:10.1097/MPH.0000000000001476

- Waris RS, Ballard M, Hong D, Seddik TB. Meningitis due to Roseomonas in an immunocompetent adolescent. Access Microbiol. 2021;3(3):000213. doi:10.1099/acmi.0.000213

- Reghu A. Bloodstream infection due to Roseomonas mucosa in a post-COVID patient. Indian J Microbiol Res. 2023;10(4):243-245.

- Matsuhisa Y, Kenzaka T, Hirose H, Gotoh T. Cellulitis caused by Roseomonas mucosa in a child: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):867. doi:10.1186/s12879-023-08875-9

- Agrawal SK, Tarai B, Sehgal S, Goldar S. Roseomonas mucosa bacteremia in an immunocompetent child. Indian J Med Spec. 2024;15(1):70-72. doi:10.4103/injms.injms_112_23

- Bhai N, Nigam C, Tewari A, Niranjan D, Paul P, et al. Atypical febrile illness caused by an emerging opportunistic pathogen Roseomonas gilardii: a case report. Open J Clin Med Case Rep. 2024;10(17):2264.