Introduction

Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma (PCACC) is rare tumor with an estimated incidence of just 0.23 cases per 1,000,000 people annually.[1] This rarity often leads to diagnostic challenges, especially when PCACC presents in atypical locations such as the scalp. Despite its low incidence, PCACC is characterized by infiltrative growth pattern, resulting in local recurrence and perineural invasion.[2] Conversely, cylindromas are benign, slow-growing scalp tumors. Both exhibit basaloid cells around hyaline material on FNAC. While histopathology and IHC remain gold standards, FNAC is often the first diagnostic tool in resource-limited settings. This underscores the need for heightened awareness of cytomorphological overlaps to prevent delayed intervention. This article explores the diagnostic complexities of PCACC, emphasizing cytological evaluation and the need for integrated diagnostic approaches in guiding appropriate treatment strategies and improving clinical outcomes.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old female presented to the surgery outpatient department with a raised swelling on the scalp. She had a history of head trauma approximately 10 years prior, and the lesion had gradually progressed over time, accompanied by seropurulent discharge for one month, without any associated pain. On examination, there was a 4 x 4 cm globular, non-mobile, firm ulcerated swelling on the scalp. The lesion was clinically suspected to be squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) due to its ulcerated appearance and location on sun-exposed scalp skin (Figure 1).

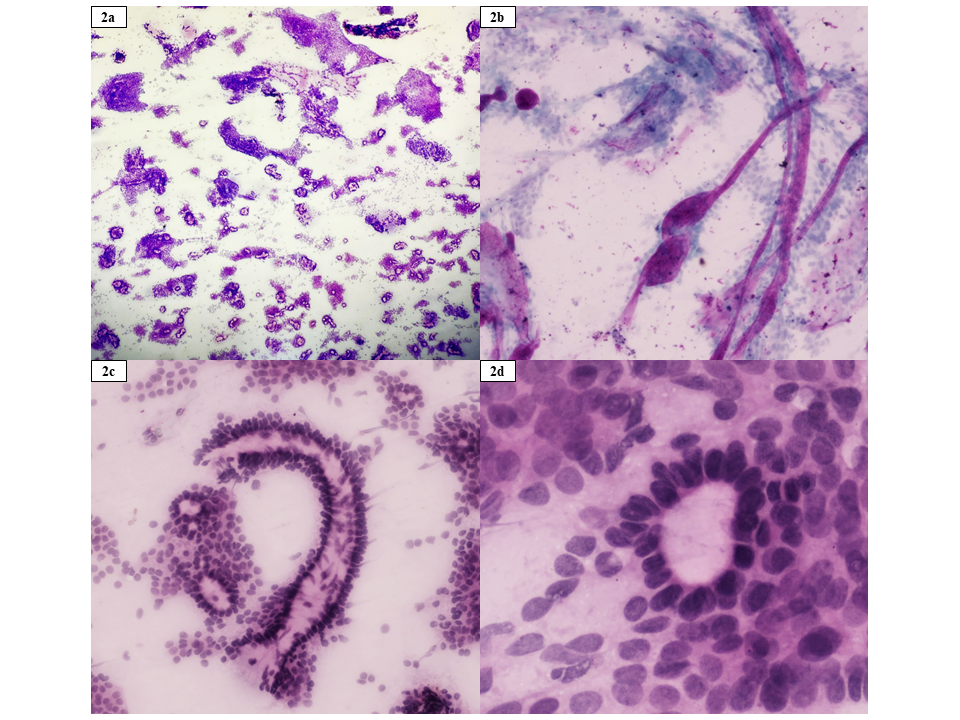

The FNAC smears stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Giemsa, and Papanicolaou (Pap), revealed high cellularity with multiple clusters of cells showing round hyperchromatic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and scant to moderate cytoplasm. The background displayed deposits of thick magenta-coloured basement membrane-like material and hyaline globules with palisading of tumor cells around them. Cribriform arrangement was also observed. PCACC and Cylindroma were considered as differential diagnoses due to overlapping cytological features (Figure 2).

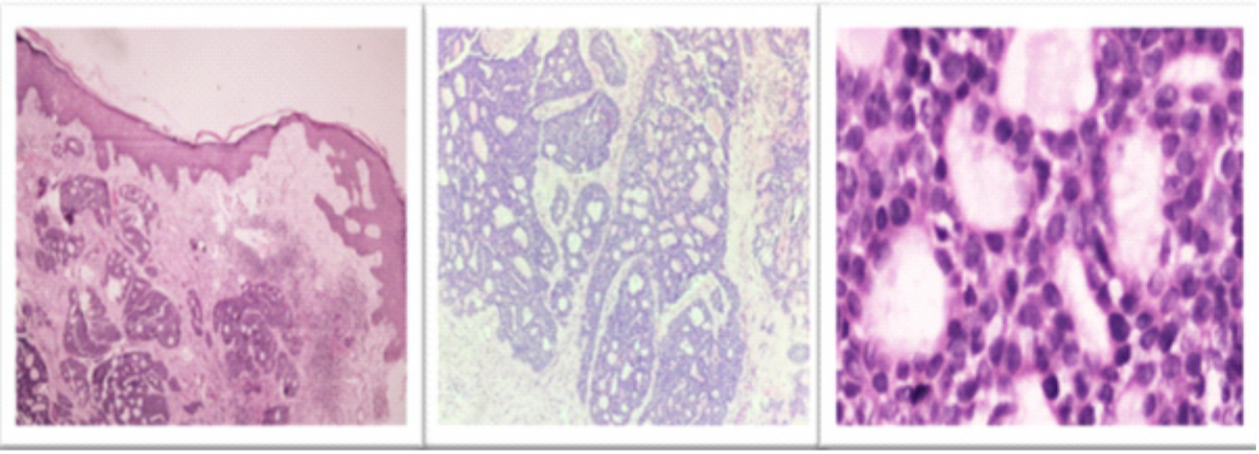

A wedge biopsy performed from the scalp swelling revealed a tissue with epidermis and dermis. The epidermis is intact. The dermis showed an unencapsulated and infiltrating tumor without any connection to the overlying epidermis in a desmoplastic stroma. The tumor is arranged predominantly in a cribriform pattern, with numerous punched-out spaces containing hyalinized material surrounded by basaloid cells. The tumor cells had round hyperchromatic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and a scant amount of cytoplasm. Mitosis was low (1-2/10 HPF). No perineural invasion noted even on multiple deeper sections examined. No keratin pearls or dyskeratotic cells were seen (Figure 3).\

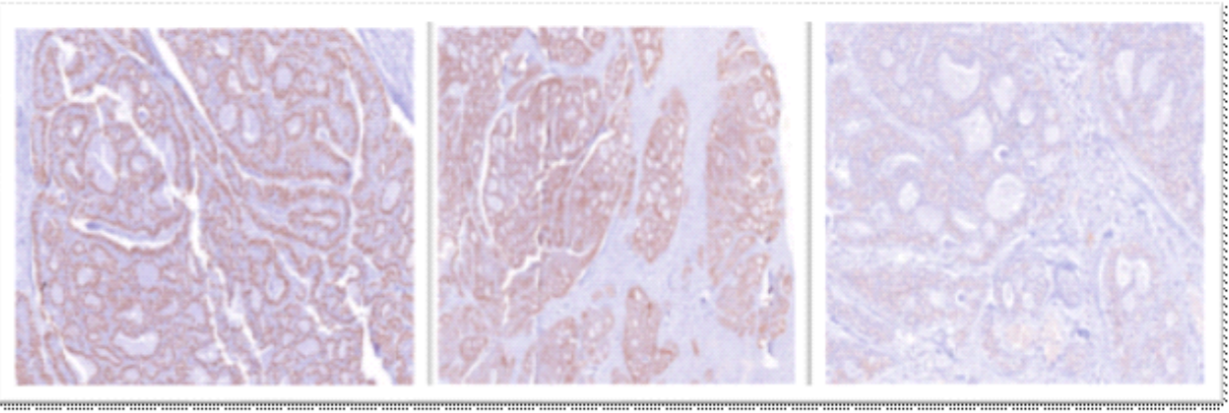

The immunohistochemical profile of the tumor demonstrated strong nuclear positivity for p63 (clone 4A4), and diffuse cytoplasmic positivity for pan-cytokeratin (AE1/AE3). In addition, focal faint cytoplasmic staining for CD117 (clone EP10) is also observed (Figure 4)

These findings collectively supported the diagnosis of PACC and aid in distinguishing it from other morphologically similar neoplasms. At 1.5-year follow-up, the patient remains disease-free without adjuvant therapy.

Discussion

PCACC is an exceptionally rare neoplasm that primarily affects the skin, often presenting as a slowly enlarging, firm, and occasionally painful nodule. PCACC is noted for its significant local invasiveness but generally has a more favourable outlook compared to salivary ACC. Although PCACC typically remains confined to the dermis, there are instances of distant metastases, usually to the lungs or regional lymph nodes, which can occur years after the initial diagnosis. This highlights the necessity for meticulous long-term surveillance.

The incidence of PCACC of is quite low primarily affecting middle-aged and elderly females. According to a population-based study in the United States, the incidence is around 0.23 per 1 million person-years. The scalp is the most common site of occurrence, accounting for about 41% of cases, with other less frequent sites including the chest, abdomen, back, eyelids, and perineum. While the Cylindromas constitutes 0.7% of all the adnexal tumors. This rarity and specific site predilection underscore the importance of accurate diagnosis.3

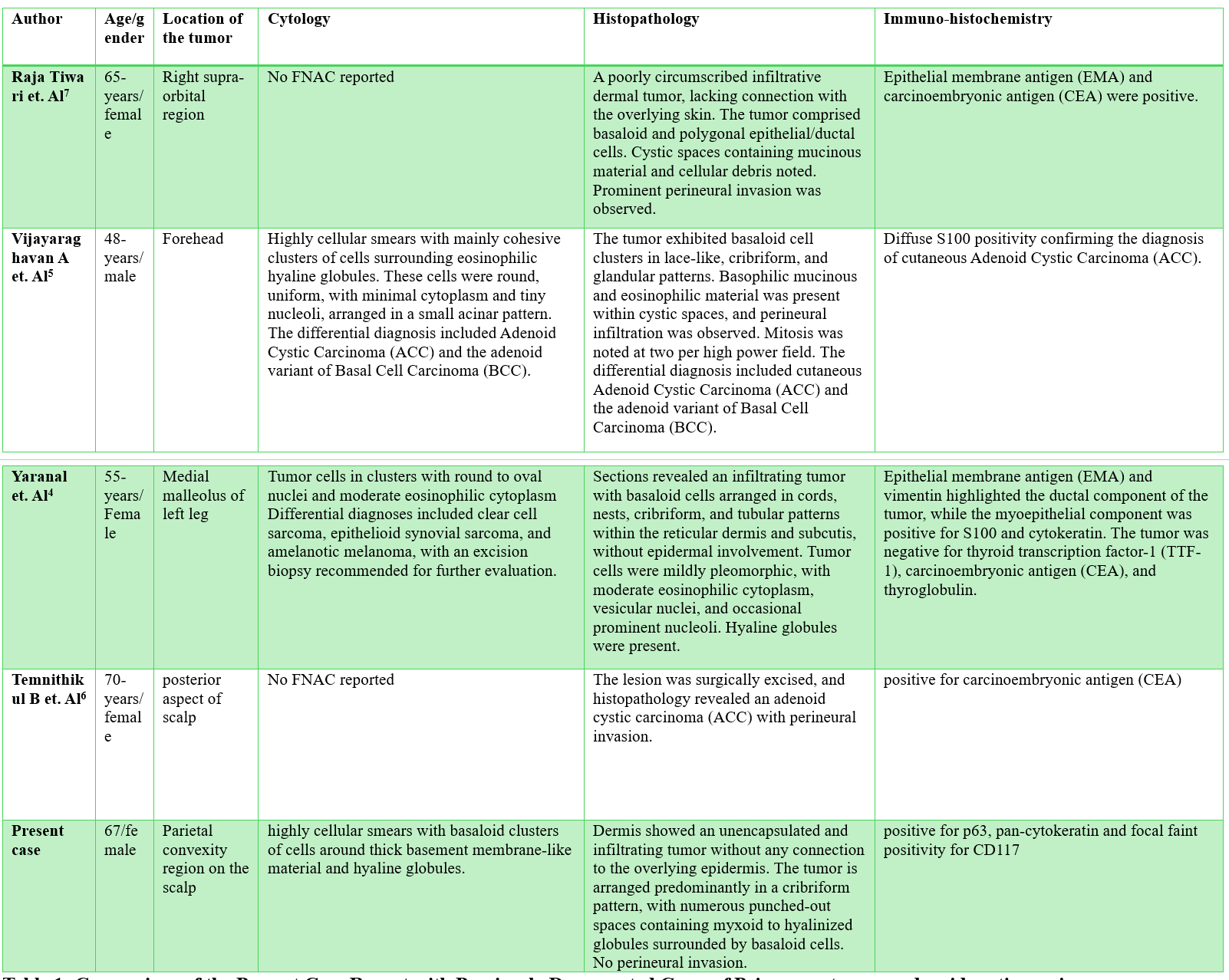

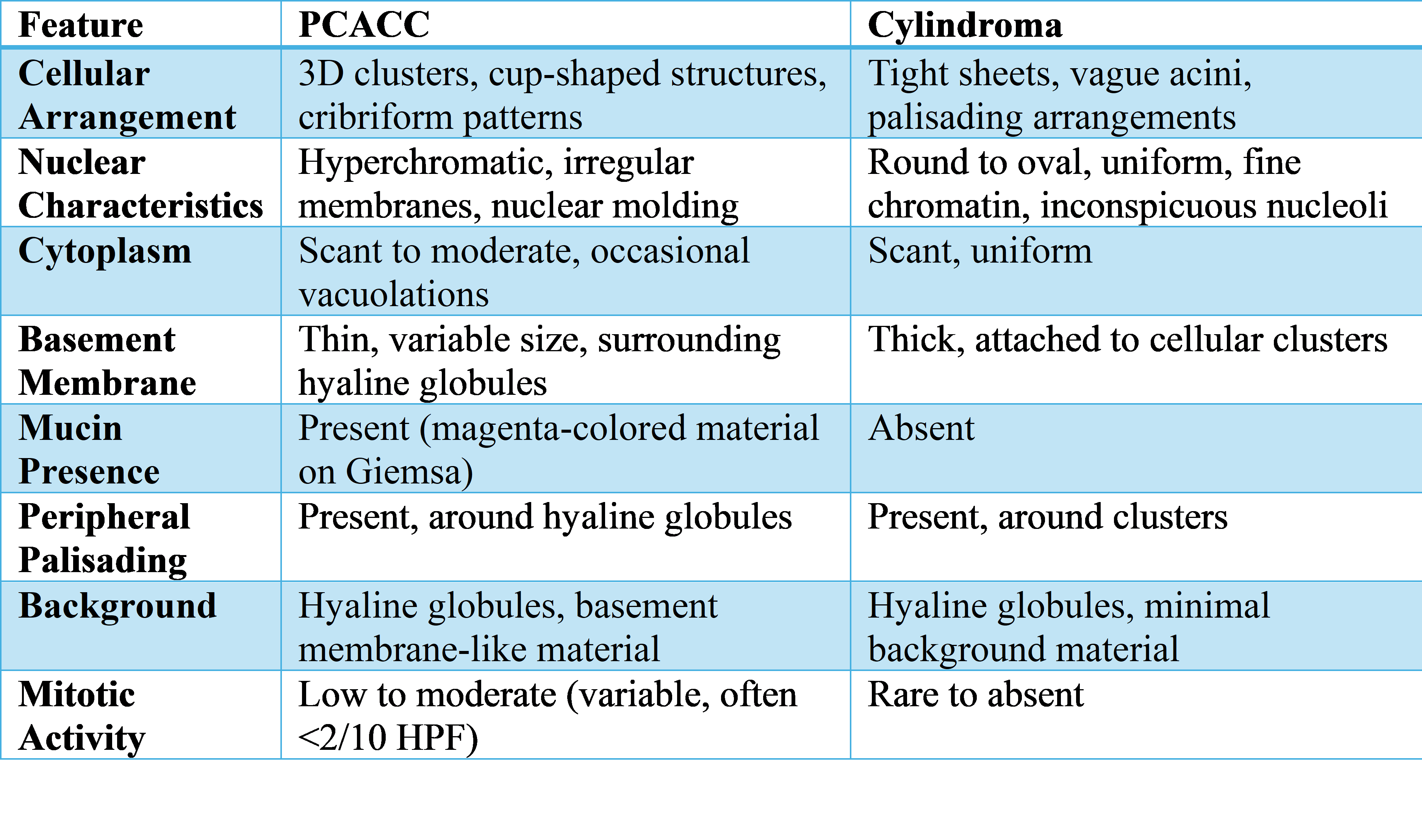

Limited case reports, such as those by Yaranal PJ et al4 and Vijayaraghavan A et al5 illustrate the challenges in diagnosing PCACC. Our study, which involved scalp swelling, emphasizes the close resemblance between Cylindroma and adenoid cystic carcinoma, highlighting the need for careful differential diagnosis using FNAC. Other reports on scalp adenoid cystic carcinoma include studies by Temnithikul B et al6, and Raja Tiwari et al7 which were diagnosed through histopathological examination. Our case report is distinctive as it presents a diagnosis made using cytological analysis. The cytological, histopathological, and immunohistochemical features described in the present case and previously reported studies are summarized in Table 1.

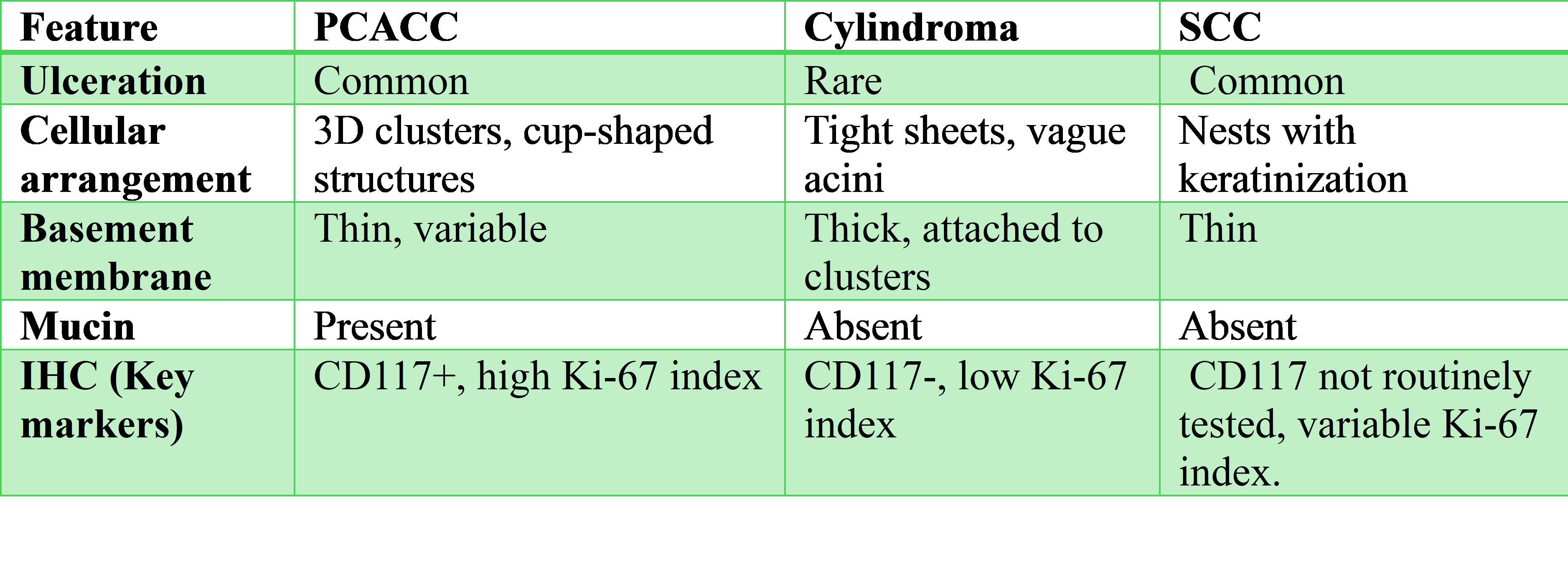

Because of its quick turnaround and low invasiveness, FNAC is an essential diagnostic technique for scalp lesions, especially in settings with limited resources.8 However, as demonstrated in this instance, there are substantial diagnostic difficulties due to the cytological overlap between cylindroma and PCACC. In our case, FNAC showed a blood-mixed, high-cellularity aspirate that initially suggested cylindroma due to the presence of basaloid cells grouped around hyaline globules, cribriform patterns, and peripheral palisading. Nevertheless, PCACC was confirmed by subsequent histopathology and immunohistochemistry (IHC), underscoring the limitations of FNAC. Based on this case and previous research, Table 2 contrasts the main cytological characteristics of PCACC and cylindroma.

Our smears (Figure 2) show that both entities exhibit peripheral palisading, which highlights their cytomorphological overlap. The lack of keratin pearls or atypical squamous differentiation made the diagnosis more difficult in this instance, ruling out SCC, but the hyaline globules and basaloid clustering looked like cylindroma. Histopathological confirmation was required to evaluate perineural or lymphovascular invasion, which is essential for PCACC diagnosis. Although precise misdiagnosis rates are still unknown, Amita et al9 report that up to 30% of scalp FNACs may be mistakenly diagnosed as cylindroma because of shared features. Given its propensity for distant metastasis and local recurrence, this overlap can postpone PCACC diagnosis in resource-constrained settings where FNAC is frequently given precedence over biopsy . It is crucial to combine FNAC with early histopathological assessment and IHC (p63, CD117, Ki-67.

Accurate differentiation between PCACC and Cylindroma through cytological examination is essential due to their differing prognoses and therapeutic requirements. Both neoplasms share overlapping cytological features which can complicate cytological diagnosis. Cylindromas are often located in hair follicle-rich areas such as the scalp and can present as solitary or multiple lesions, sometimes resembling a "turban" due to their appearance as seen in our case. In contrast, PCACC has distinctive features including perineural invasion and a tendency for distant metastases.10 Accurate differentiation is vital due to PCACC's aggressive nature and need for intensive treatment, including surgery and possibly adjuvant therapies. Misdiagnosis as Cylindroma, which is typically benign, can lead to inadequate treatment and worse outcomes due to delayed intervention and improper management strategies. Further studies are needed to estimate FNAC misdiagnosis prevalence. PCACC may clinically mimic SCC due to ulceration, firm consistency, and occurrence in sun-exposed areas. Notably, SCC typically presents with Keratin pearls and atypical keratinocytes on cytology which were absent in our case (Table 3).

Conclusion

This case highlights that PCACC, though rare, can clinically resemble SCC or other ulcerated malignancies. Although FNAC is a useful diagnostic tool, its ability to distinguish between primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma (PCACC) and Cylindroma is limited because of their substantial cytomorphological overlap. Early consideration of histopathological examination and immunohistochemistry, particularly markers like p63, CD117, and Ki-67, is highly advised in cases of scalp lesions with unclear cytologic features. By integrating these findings into clinical practice, healthcare providers can enhance diagnostic precision, optimize treatment strategies, and ensure effective patient care.

Consent and ethics

Written informed consent was waivered as the data was completely anonymised.

References

- Dores GM, Huycke MM, Devesa SS, Garcia CA. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma in the United States: incidence, survival, and associated cancers, 1976 to 2005. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010 Jul;63(1):71-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.07.027. Epub 2010 May 5.

- Prieto-Granada CN, Zhang L, Antonescu CR, Henneberry JM, Messina JL. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma with MYB aberrations: report of three cases and comprehensive review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2017 Feb;44(2):201-209. doi: 10.1111/cup.12856. Epub 2016 Dec 2.

- Raychaudhuri S, Santosh KV, Satish Babu HV. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma of the chest wall: a rare entity. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012 Oct-Dec;8(4):633-5. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.106583.

- Yaranal PJ, Bithun BK, Anand AS. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma - An onerous task for clinicians and pathologists. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2022;65(2):459–61.

- Vijayaraghavan A, Ramamoorthy S, Theresa SM, Srinivasamurthy BC, Sinhasan SP.Recurrent Cutaneous Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma of Forehead.J Clin of Diagn Res.2021; 15(10):ED04-ED06. https://www.doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2021/51034/15510

- Temnithikul B, Rungrunanghiranya S, Limtanyakul P, Jerasuthat S, Paige DG. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma of the scalp: A case report, immunohistochemistry and review of the literature. Skin Health Dis. 2022 Apr 28;2(2):e118.

- Tiwari R, Agarwal S, Sharma M, Gaba S. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma: A clinical and histopathological mimic: A case report. Oral Maxillofac Surg Cases. 2018 Dec 1;4(4):175–9.

- Spitz DJ, Reddy V, Selvaggi SM, Kluskens L, Green L, Gattuso P. Fine-needle aspiration of scalp lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000 Jul;23(1):35-8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0339(200007)23:1

- Amita K, Pournami SV, Rashmi R, Kusuma KN, Priyadarshini P, Recurrent cylindroma of the scalp: a cytomorphological evaluation at fine needle aspiration cytology. Cureus. 2022 May 19;14(5).

- Hurt MA, Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2010. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2012 Jan 31;2(1):79–82. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0201a15.