Introduction

Anastomosing haemangioma (AH) is a recently characterized benign vascular neoplasm with distinct histopathological features. It often mimics aggressive vascular tumors such as angiosarcoma. AH typically exhibits a sinusoidal network of capillary-calibre vessels which is lined by hobnail endothelial cells with an overall architecture that recalls the red pulp of the spleen [1]. Although benign, its presentation can raise considerable clinical concern particularly when arising in deep visceral or retroperitoneal locations. The genitourinary tract, especially the kidney, remains the most commonly reported site, accounting for the majority of documented cases. The age of presentation ranges widely—from the fourth to the eighth decade—with no consistent gender predilection. Most cases are identified incidentally during imaging for unrelated complaints. These lesions may simulate invasive malignancy on both imaging and intraoperative assessment when large or involving multiple contiguous structures. This is more so in retroperitoneal presentations where apparent tissue infiltration may mimic malignant behavior [2].

Anastomosing hemangiomas of the retroperitoneum are rare, with even fewer reports describing contiguous involvement of both the kidney and liver. Retroperitoneal lesions particularly those located in proximity to the adrenal gland or upper renal pole may demonstrate radiologic features that are concerning for renal cell carcinoma (RCC), adrenal cortical carcinoma or even metastatic disease.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) and MRI often reveal heterogeneously enhancing soft tissue masses. These imaging findings may lead to a presumptive diagnosis of malignant neoplastic pathology. When these lesions exhibit infiltration or mass effect on neighboring organs such as the liver surgical planning often leans toward radical intervention to ensure oncologic adequacy. The implications are significant: patients may undergo nephrectomy, hepatic resection or adrenalectomy with the associated morbidity of major organ removal despite the lesion's benign pathology [3].

The radiologic ambiguity of AH is well-documented. Imaging such as CECT usually shows hypervascular lesions with cystic or hemorrhagic changes, slow contrast washout and indistinct margins can easily mimic malignancies such as RCC, angiosarcoma or hepatic hemangioendothelioma. Furthermore, when intraoperative findings reveal firm adherence to critical structures the surgeon is often compelled to proceed with en bloc resection. The role of image-guided biopsy or intraoperative frozen section remains underutilized in reported literature, partly due to concerns about sampling error in vascular lesions and the difficulty in distinguishing benign from malignant vascular tumors based on small tissue samples [4].

Histologically, AH is characterized by well-formed, anastomosing vascular channels lined by a single layer of bland endothelial cells often with hobnail morphology. These are typically set in a fibrotic or edematous stroma and lack cytologic atypia and mitotic activity which are features that are hallmarks of angiosarcoma. AH consistently expresses endothelial markers such as CD31, CD34, and ERG, and shows a low Ki-67 proliferation index [5].

These immunohistochemistry features enable clear distinction from more aggressive vascular neoplasms. Therefore, preoperative recognition of AH requires expert pathological review and adequate tissue sampling.

This case of retroperitoneal AH with contiguous involvement of the kidney and liver is exceedingly rare and represents an anatomically and diagnostically challenging variant of an already uncommon entity.

Case presentation

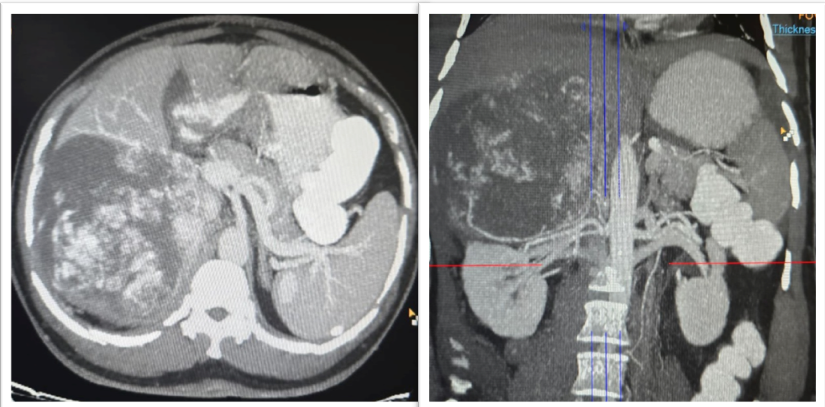

A 56-year-old man presented with a two-week history of vague, dull aching pain in the right upper abdomen. There were no accompanying constitutional symptoms such as fever, anorexia or weight loss. He was a known case of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. On general examination, he was conscious, oriented, and hemodynamically stable. Abdomen was soft, non-tender without any palpable mass. Systemic examination was unremarkable. Baseline laboratory investigations such as complete blood count, renal and liver function tests were within normal limits. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed minimal right-sided pleural effusion. Scrotal ultrasonography showed bilateral grade IV varicocele with a small right hydrocele, which was considered incidental. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen demonstrated a large, well-defined heterogeneously enhancing retroperitoneal mass in the right upper quadrant measuring approximately 20 × 10 cm. The lesion was inseparable from the upper pole of the right kidney and showed apparent extension into hepatic segments VI and VII, raising strong suspicion of a malignant neoplasm, most likely renal cell carcinoma with hepatic involvement (Figure 1).

In view of the radiologic findings and suspected multi-organ involvement surgical exploration was planned. At exploratory laparotomy, a large, firm, highly vascular retroperitoneal mass was identified in the right upper abdomen. The mass was densely adherent to the upper pole of the right kidney and closely related to adjacent structures including the retro hepatic region. Due to the inability to safely separate the lesion from the renal parenchyma and the strong intraoperative suspicion of malignancy, complete excision of the retroperitoneal mass with right radical nephrectomy and non-anatomical resection of hepatic segments VI and VII was performed.Gross examination of the specimen comprising retroperitoneal mass excision with right nephrectomy, measured 20.4 × 14.3 × 8.4 cm. An irregular thin rim of liver parenchyma measuring 9.6 × 4 cm and a small part of diaphragm measuring 3.7 × 1.9 cm were also identified. The right kidney measured 12.1 × 5.5 × 4.5 cm with an attached ureter measuring 6 cm in length. A well-circumscribed tumor measuring 12.4 × 10.2 × 9.6 cm was seen on the superomedial surface of the kidney. The anterior surface of the mass was covered by peritoneum, while the posterior surface was covered by retroperitoneal adipose tissue. On cut section, the tumor was lobulated, soft to focally spongiform in consistency, and pale yellowish-brown in color, with areas of edema and myxoid change. Focal hemorrhage and approximately 5% necrosis were noted. The tumor was firmly adherent to the renal capsule, hepatic capsule, and a small portion of diaphragm; however, gross direct parenchymal infiltration into the kidney or liver was not identified. The intervening tissue between the tumor and liver showed a flattened adrenal gland measuring 4.5 × 3.2 × 0.5 cm, with the tumor appearing to surround the adrenal gland. The lower pole of the kidney showed a benign subcapsular cyst measuring 1.5 × 1.5 cm filled with necrotic brownish material, while the remaining renal parenchyma and pelvicalyceal system were unremarkable (Figure 2).

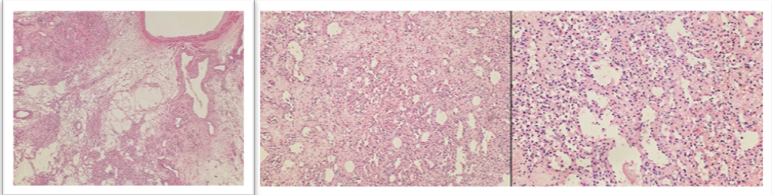

Microscopic examination of multiple sections from the retroperitoneal mass showed a well-circumscribed and encapsulated neoplasm with a vaguely lobulated growth pattern. The lobules were composed of irregular capillary-sized vascular spaces arranged in a prominent anastomosing configuration. These vascular channels were lined by a single layer of round to oval endothelial cells exhibiting frequent hobnail morphology. The nuclei showed minimal atypia with bland chromatin, and mitotic figures were infrequent. Focal intravascular fibrin thrombi and extravasated red blood cells were present. In addition, focal intraluminal collections of erythroid cells with occasional megakaryocytes were identified. The stroma was predominantly edematous to hyalinized with focal myxoid change and showed proliferation of elongated smooth muscle cells. At the periphery, several large muscularized feeder vessels and a few entrapped adipocytes were seen. Lipoblasts, atypical pleomorphic stromal cells or high-grade sarcomatous areas were not identified. In a few sections, the tumor was in direct continuity with adrenal gland parenchyma and extended into periadrenal soft tissue, causing firm adhesion to the renal and hepatic capsule; however, direct microscopic infiltration into renal or hepatic parenchyma was not identified (Figure 3).

On immunohistochemistry, the endothelial cells lining the vascular spaces showed diffuse strong positivity for CD34. HMB45 and Melan-A were negative. Smooth muscle actin was negative in endothelial cells but positive in supporting stromal cells. The Ki-67 proliferation index was less than 1%, supporting a benign vascular neoplasm.All resection margins, including retroperitoneal soft tissue margin, renal vascular and ureteric margins, hepatic parenchymal margin, and diaphragmatic margin, were uninvolved by tumor. The non-neoplastic renal parenchyma showed occasional sclerosed glomeruli with mild periglomerular fibrosis, focal mild tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and patchy interstitial inflammation adjacent to the site of tumor adhesion, along with hyaline arteriolosclerosis and mild medial hypertrophy of blood vessels. The included hepatic parenchyma showed maintained acinar architecture with sparse portal lymphomononuclear infiltrate, mild macrovesicular steatosis involving approximately 5–10% of hepatocytes, and a few ballooned hepatocytes with Mallory–Denk bodies. There was no interface hepatitis, confluent necrosis, or significant parenchymal fibrosis on Masson trichrome staining, and no evidence of hepatocellular carcinoma.Based on the characteristic histomorphological features and immunohistochemical profile, a final diagnosis of retroperitoneal anastomosing haemangioma was rendered, with no evidence of malignancy. The postoperative period was uneventful. At the time of follow-up visit at 3 months postoperatively the patient was found to be asymptomatic with no clinical or radiologic evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

The present case describes a large anastomosing haemangioma (AH) of the retroperitoneum which involved kidney as well as liver. This is an extremely rare presentation that posed significant diagnostic as well as surgical challenges. The lesion was relatively large and inseparable from the upper pole of the right kidney. It also showed apparent hepatic extension on imaging which aroused suspicion of a malignant pathology. Berker NK in their study of 49 AH cases highlighted how these tumors usually exhibit infiltrative margins and appear hypervascular on imaging. These features lead to misdiagnoses such as angiosarcoma or renal cell carcinoma (RCC) thereby prompting radical surgeries [6]. Song J et al likewise observed that AH of the kidney could be mistaken for RCC in many cases. This often results in radical nephrectomy as was necessary in our case due to intraoperative suspicion of malignancy [7].

On imaging the lesion in our patient appeared as a heterogeneously enhancing retroperitoneal mass. It was having ill-defined borders, slow contrast washout and suspected hepatic invasion. These findings were indistinguishable from malignant neoplasms. These imaging features necessitated a radical surgical approach including nephrectomy and hepatic segmental resection. Comparable imaging characteristics were reported by Xue X et al who emphasized that AH can mimic invasive carcinomas resulting in extended surgical resections [8]. Similarly, Omiyale AO reviewed vascular lesions of the retroperitoneum and kidney and emphasized the absence of definitive radiologic criteria to distinguish benign AH from aggressive vascular or renal malignancies often leading to extensive surgical interventions in many patients [9]. Histopathologically, our case revealed a well-circumscribed vascular lesion having anastomosing capillary-sized channels which were lined by bland hobnail endothelial cells. There was no evidence of cytologic atypia or mitotic activity. Immunohistochemistry showed diffuse CD34 positivity and Ki-67 index of less than 1%.

These findings were diagnostic of a benign vascular pathology. This was also in line with the histomorphologic criteria established by Montgomery and Epstein who described AH as a benign lesion with anastomosing vessels characteristically lacking the cytologic atypia and mitoses [10]. Chang Chien YC et al further supported these distinctions in their analysis of vascular tumors of the kidney. The authors therefore emphasised the diagnostic utility of immunohistochemistry and careful morphologic assessment [11]. In our case the final diagnosis was made only after extensive resection and thorough histopathologic evaluation.

Interestingly, intraoperatively, the lesion in our case was densely adherent to the renal capsule and hepatic capsule. There was an apparent encasement of the adrenal gland which heightened concern for malignancy. However, histologic analysis confirmed no direct parenchymal invasion. This behavior resembles the “pseudoinfiltrative” pattern described by Lin et al who reported that AH can appear adherent or even infiltrative grossly and radiologically yet maintain benign histologic features without true tissue invasion [12]. Brown JG et al similarly discussed that AH may involve multiple contiguous structures or be surrounded by reactive changes which can mimic locally invasive malignancies and complicate intraoperative decision-making [13].

Our patient had no recurrence or residual symptoms at three-month follow-up. This was consistent with the benign nature of AH. No evidence of malignancy or recurrence has been reported in literature following complete excision in cases of AH. Zhang et al in their case of AH found no recurrence after surgical removal even after 40 months [14]. Wang Z et al reached similar conclusions in their evaluation of ovarian AH reiterating that despite alarming clinical and radiologic presentations these tumors consistently behaved in an indolent manner [15]. Our case adds to this growing body of literature and supports the recommendation for conservative management when AH is confidently diagnosed preoperatively.

Conclusion

Retroperitoneal anastomosing haemangioma is a rare benign vascular neoplasm that can closely mimic malignancy on imaging and at surgery, especially when large and adherent to contiguous organs. Our case with apparent renal and hepatic involvement resulted in radical resection due to strong preoperative and intraoperative suspicion of carcinoma. Recognition of its characteristic hobnail, anastomosing vascular pattern with low proliferative index is essential to avoid over treatment and morbidity.

Consent and ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication.

References

- Shanbhogue K, Khandelwal A, Hajdu C, Cao W, Surabhi VR, Prasad SR. Anastomosing haemangioma: a current update on clinical, pathological and imaging features. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2022 Jul;47(7):2335-2346. doi:10.1007/s00261-022-03559-5. Epub 2022 Jun 9.

- Rezk A, Richards S, Castillo RP, Schlumbrecht M. Anastomosing haemangioma of the ovary mimics metastatic ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2020 Sep 17;34:100647. doi:10.1016/j.gore.2020.100647.

- Apinha MD, Carvalho-Dias E, Cerqueira-Alves M, Mota P. Renal anastomosing haemangioma. BMJ Case Rep. 2023 Sep 18;16(9):e254131. doi:10.1136/bcr-2022-254131.

- Merritt B, Behr S, Umetsu SE, Roberts J, Kolli KP. Anastomosing haemangioma of liver. J Radiol Case Rep. 2019 Jun 30;13(6):32-39. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v13i6.3644.

- Muñoz-Caicedo B, García-Gómez V, Gutiérrez C, Noreña-Rengifo B, Muñoz-Caicedo J. Unraveling anastomosing hemangioma: a case report. Cureus. 2024 Mar 1;16(3):e55351. doi:10.7759/cureus.55351.

- Berker NK, Bayram A, Tas S, Bakir B, Caliskan Y, Ozcan F, Kilicaslan I, Ozluk Y. Comparison of renal anastomosing hemangiomas in end-stage and non-end-stage kidneys: a meta-analysis with a report of 2 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2017 Sep;25(6):488-496. doi:10.1177/1066896917706025. Epub 2017 Apr 24.

- Song J, Peng C, Ding X, Guo H, Chen Y, Khoo H, Mou L, Jiao Q, Bai X, Shi C, Zou N, Li X, Li Z, Zhang X, Ma X, Huang Q. A case series and literature review of renal anastomosing haemangioma: an often-misdiagnosed benign tumor. Curr Urol. 2025 Nov;19(6):423-428. doi:10.1097/CU9.0000000000000298. Epub 2025 Aug 14.

- Xue X, Song M, Xiao W, Chen F, Huang Q. Imaging findings of retroperitoneal anastomosing haemangioma: a case report and literature review. BMC Urol. 2022 May 22;22(1):77. doi:10.1186/s12894-022-01022-7.

- Omiyale AO. Primary vascular tumours of the kidney. World J Clin Oncol. 2021 Dec 24;12(12):1157-1168. doi:10.5306/wjco.v12.i12.1157.

- Montgomery E, Epstein JI. Anastomosing haemangioma of the genitourinary tract: a lesion mimicking angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009 Sep;33(9):1364-1369. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ad30a7.

- Chang Chien YC, Beke L, Méhes G, Mokánszki A. Anastomosing hemangioma: report of three cases with molecular and immunohistochemical studies and comparison with well-differentiated angiosarcoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2022 Aug 1;28:1610498. doi:10.3389/pore.2022.1610498.

- Lin J, Bigge J, Ulbright TM, Montgomery E. Anastomosing haemangioma of the liver and gastrointestinal tract: an unusual variant histologically mimicking angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013 Nov;37(11):1761-1765. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182967e6c.

- Brown JG, Folpe AL, Rao P, Lazar AJ, Paner GP, Gupta R, Parakh R, Cheville JC, Amin MB. Primary vascular tumors and tumor-like lesions of the kidney: a clinicopathologic analysis of 25 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010 Jul;34(7):942-949. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e4f32a.

- Zhang L, Wu J. Multimodal imaging features of retroperitoneal anastomosing haemangioma: a case report and literature review. Front Oncol. 2023 Oct 25;13:1269631. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1269631. PMID:37954079.

- Wang Z, Hu J. A case report of anastomosing haemangioma of the ovary. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023 May 12;102(19):e33801. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000033801.